عمالة الأطفال

Child labour refers to the exploitation of children through any form of work that deprives them of their childhood,[3] interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful.[4] Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation worldwide,[5][6] although these laws do not consider all work by children as child labour; exceptions include work by child artists, family duties, supervised training, and some forms of work undertaken by Amish children, as well as by indigenous children in the Americas.[7][8][9]

Child labour has existed to varying extents throughout history. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, many children aged 5–14 from poorer families worked in Western nations and their colonies alike. These children mainly worked in agriculture, home-based assembly operations, factories, mining, and services such as news boys – some worked night shifts lasting 12 hours. With the rise of household income, availability of schools and passage of child labour laws, the incidence rates of child labour fell.[10][11][12]

اعتبارا من 2023[تحديث], in the world's poorest countries, around one in five children are engaged in child labour, the highest number of whom live in sub-saharan Africa, where more than one in four children are so engaged.[13] This represents a decline in child labour over the preceding half decade.[14] In 2017, four African nations (Mali, Benin, Chad and Guinea-Bissau) witnessed over 50 percent of children aged 5–14 working.[14] Worldwide agriculture is the largest employer of child labour.[15] The vast majority of child labour is found in rural settings and informal urban economies; children are predominantly employed by their parents, rather than factories.[16] Poverty and lack of schools are considered the primary cause of child labour.[17] UNICEF notes that "boys and girls are equally likely to be involved in child labour", but in different roles, girls being substantially more likely to perform unpaid household labour.[13]

Globally the incidence of child labour decreased from 25% to 10% between 1960 and 2003, according to the World Bank.[18] Nevertheless, the total number of child labourers remains high, with UNICEF and ILO acknowledging an estimated 168 million children aged 5–17 worldwide were involved in child labour in 2013.[19]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

تعريفات

الطفولة

إذا توجهت بالسؤال التالي : ما هي الطفولة ؟ إلى أي شخص ، فماذا سيكون رده يا ترى ؟ من المؤكد بأن الإجابات ستختلف من شخص لآخر ، كما تختلف من علم لآخر ، لأن كل شخص ينظر إلى الطفل بمنظوره هو ، و بمدى تأثره بالأطفال . لكن التعريف الأصح هو الذي خلص إليه علماء النفس و التربية ، و هم المعنيون بدراسة التركيبة الإنسانية خلال مراحل الحياة ، و هو أن :

( الطفولة هي المرحلة العمرية التي تمتد من سن الولادة إلى سن الثانية عشر تقريباً )

و هذه المرحلة العمرية بدورها تنقسم إلى ثلاث مراحل فرعية تتميز كل منها بعدة خصائص و مميزات ، و هذه المراحل الفرعية هي :

1 - الطفولة المبكرة (3-5) سنوات .

2 - الطفولة المتوسطة (6-8) سنوات .

3 - الطفولة المتأخرة (9-11) سنوات .

إن تقسيم العلماء لدورة حياة الإنسان إلى مراحل متعددة لا يأتي من فراغ ، و إنما جاء هذا التقسيم على أساس اختلاف خصائص كل مرحلة من مراحل عمر الإنسان عن المراحل الأخرى ، و حتى ندرك مدى أهمية هذه المرحلة العمرية التي يمر بها الإنسان ، يجب أن نتعرف أولا على خصائص هذه المرحلة . و خصائص هذه المرحلة متنوعة و متعددة إلا أننا سنكتفي بذكر ثلاث منها على علاقة بموضوع الندوة :

1 - الطفولة مرحلة ضعف .

و نعني بقولنا هذا ، أن الطفل في هذه المرحلة لم يصل إلى مرحلة النضج التكويني ، التي تؤهله لأن يكون إنسانا كاملا قادرا على العطاء و الإنتاج ، فهو – أن قارناه بالإنسان الذي ينتمي إلى مرحلة عمرية مختلفة عنه – يعتبر ضعيفاً ، و يتمثل هذا الضعف في كثير من الجوانب ، مثل : القدرة على التعبير ، و تحمل المسؤولية ،و الضعف البدني و العقلي .

2 - الطفولة مرحلة بناء .

أي أن الطفل يكون في هذه المرحلة في طور البناء و التكوين ، و يملك من الاستعدادات الفطرية ما يؤهله للضلوع بهذه المهمة ، و من الممكن ملاحظة ذلك من خلال المقارنة بين الطفل و الشخص البالغ ، حيث أن الطفل يستطيع أن يتعلم بسرعة اللغة التي يتحدث الأشخاص بها من حوله ، و لكن الإنسان البالغ يصعب عليه تعلم لغة جديدة غير لغته الأم التي تعلمها في الصغر .

3 - الطفولة مرحلة محدودة .

بمعنى أن تعويض هذه المرحلة لا يمكن أن يتم في مراحل عمرية لاحقة ، و في هذا الموضوع يقول علماء التربية بأن الاعتقاد بأن بناء الإنسان يمكن أن يتم في المراحل العمرية التي تلي مرحلة الطفولة اعتقاد خاطئ ، فهذه المراحل لا تتعدى أن تكون نسخة طبق الأصل من مرحلة الطفولة .

العمالة

( منظومة قوى الانتاج في أي مجال من مجالات العمل المجازة و المعتمدة من قبل الهيئات المختصة ( وزارات العمل ) و هي لا تجيز أي إنسان إلا بعد أن يصل إلى السن القانونية للعمل ) و هذا يعني بأن الإنسان المؤهل للعمل ، و الذي تسمح له الهيئات المختصة بالعمل يجب أن يتجاوز سنا قانونية معينة ، و إلا فإن دخول هذا الإنسان لميدان العمل يعتبر عملا مخالفا للقانون . و بعد أن تعرفنا في الجزء الأول من هذا المحور على تعريف مرحلة الطفولة و أهم خصائصها ، نستطيع القول بأن الإنسان الذي ينتمي إلى هذه المرحلة العمرية ، هو إنسان غير مهيأ للوفاء بالمتطلبات المهنية ، و هو في نفس الوقت لم يتعد السن القانونية للعمل .

History

Child labour in preindustrial societies

Child labour forms an intrinsic part of pre-industrial economies.[20][21] In pre-industrial societies, there is rarely a concept of childhood in the modern sense. Children often begin to actively participate in activities such as child rearing, hunting and farming as soon as they are competent. In many societies, children as young as 13 are seen as adults and engage in the same activities as adults.[20]

The work of children was important in pre-industrial societies, as children needed to provide their labour for their survival and that of their group.[22] Pre-industrial societies were characterised by low productivity and short life expectancy; preventing children from participating in productive work would be more harmful to their welfare and that of their group in the long run. In pre-industrial societies, there was little need for children to attend school. This is especially the case in non-literate societies. Most pre-industrial skill and knowledge were amenable to being passed down through direct mentoring or apprenticing by competent adults.[20]

Child labourers, Macon, Georgia, 1909

Two girls protesting child labour (by calling it child slavery) in the 1909 New York City Labor Day parade.

Arthur Rothstein, Child Labor, Cranberry Bog, 1939. Brooklyn Museum

Industrial Revolution

With the onset of the Industrial Revolution in Britain in the late 18th century, there was a rapid increase in the industrial exploitation of labour, including child labour. Industrial cities such as Birmingham, Manchester, and Liverpool rapidly grew from small villages into large cities and improving child mortality rates. These cities drew in the population that was rapidly growing due to increased agricultural output. This process was replicated in other industrialising countries.[23]

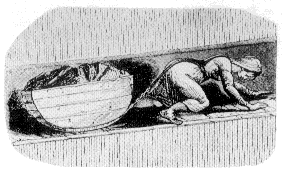

The Victorian era in particular became notorious for the conditions under which children were employed.[24] Children as young as four were employed in production factories and mines working long hours in dangerous, often fatal, working conditions.[25] In coal mines, children would crawl through tunnels too narrow and low for adults.[26] Children also worked as errand boys, crossing sweepers, shoe blacks, or selling matches, flowers and other cheap goods.[27] Some children undertook work as apprentices to respectable trades, such as building or as domestic servants (there were over 120,000 domestic servants in London in the mid-18th century). Working hours were long: builders worked 64 hours a week in the summer and 52 hours in winter, while servants worked 80-hour weeks.[28]

Child labour played an important role in the Industrial Revolution from its outset, often brought about by economic hardship. The children of the poor were expected to contribute to their family income.[27] In 19th-century Great Britain, one-third of poor families were without a breadwinner, as a result of death or abandonment, obliging many children to work from a young age. In England and Scotland in 1788, two-thirds of the workers in 143 water-powered cotton mills were described as children.[29] A high number of children also worked as prostitutes.[30] The author Charles Dickens worked at the age of 12 in a blacking factory, with his family in debtor's prison.[31]

Child wages were often low, the wages were as little as 10–20% of an adult male's wage.[32][مطلوب مصدر أفضل] Karl Marx was an outspoken opponent of child labour,[33] saying British industries "could but live by sucking blood, and children’s blood too", and that U.S. capital was financed by the "capitalized blood of children".[34][35] Letitia Elizabeth Landon castigated child labour in her 1835 poem The Factory, portions of which she pointedly included in her 18th Birthday Tribute to Princess Victoria in 1837.

Throughout the second half of the 19th century, child labour began to decline in industrialised societies due to regulation and economic factors because of the Growth of trade unions. The regulation of child labour began from the earliest days of the Industrial Revolution. The first act to regulate child labour in Britain was passed in 1803. As early as 1802 and 1819 Factory Acts were passed to regulate the working hours of workhouse children in factories and cotton mills to 12 hours per day. These acts were largely ineffective and after radical agitation, by for example the "Short Time Committees" in 1831, a Royal Commission recommended in 1833 that children aged 11–18 should work a maximum of 12 hours per day, children aged 9–11 a maximum of eight hours, and children under the age of nine were no longer permitted to work. This act however only applied to the textile industry, and further agitation led to another act in 1847 limiting both adults and children to 10-hour working days. Lord Shaftesbury was an outspoken advocate of regulating child labour.[بحاجة لمصدر]

As technology improved and proliferated, there was a greater need for educated employees. This saw an increase in schooling, with the eventual introduction of compulsory schooling. Improved technology, automation and further legislation significantly reduced child labour particularly in western Europe and the U.S.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Early 20th century

| Census year | % boys aged 10–14 as child labour |

|---|---|

| 1881 | 22.9 |

| 1891 | 26.0 |

| 1901 | 21.9 |

| 1911 | 18.3 |

| Note: These are averages; child labour in Lancashire was 80% | |

| Source: Census of England and Wales | |

In the early 20th century, thousands of boys were employed in glass making industries. Glass making was a dangerous and tough job especially without the current technologies. The process of making glass includes intense heat to melt glass (3,133 °F (1,723 °C)). When the boys are at work, they are exposed to this heat. This could cause eye trouble, lung ailments, heat exhaustion, cuts, and burns. Since workers were paid by the piece, they had to work productively for hours without a break. Since furnaces had to be constantly burning, there were night shifts from 5:00 pm to 3:00 am. Many factory owners preferred boys under 16 years of age.[37]

An estimated 1.7 million children under the age of fifteen were employed in American industry by 1900.[38]

In 1910, over 2 million children in the same age group were employed in the United States.[39] This included children who rolled cigarettes,[40] engaged in factory work, worked as bobbin doffers in textile mills, worked in coal mines and were employed in canneries.[41] Lewis Hine's photographs of child labourers in the 1910s powerfully evoked the plight of working children in the American south. Hine took these photographs between 1908 and 1917 as the staff photographer for the National Child Labor Committee.[42]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Household enterprises

Factories and mines were not the only places where child labour was prevalent in the early 20th century. Home-based manufacturing across the United States and Europe employed children as well.[10] Governments and reformers argued that labour in factories must be regulated and the state had an obligation to provide welfare for poor. Legislation that followed had the effect of moving work out of factories into urban homes. Families and women, in particular, preferred it because it allowed them to generate income while taking care of household duties.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Home-based manufacturing operations were active year-round. Families willingly deployed their children in these income generating home enterprises.[43] In many cases, men worked from home. In France, over 58% of garment workers operated out of their homes; in Germany, the number of full-time home operations nearly doubled between 1882 and 1907; and in the United States, millions of families operated out of home seven days a week, year round to produce garments, shoes, artificial flowers, feathers, match boxes, toys, umbrellas and other products. Children aged 5–14 worked alongside the parents. Home-based operations and child labour in Australia, Britain, Austria and other parts of the world was common. Rural areas similarly saw families deploying their children in agriculture. In 1946, Frieda S. Miller – then Director of the United States Department of Labor – told the International Labour Organization (ILO) that these home-based operations offered "low wages, long hours, child labour, unhealthy and insanitary working conditions".[10][44][45][46]

21st century

Child labour is still common in many parts of the world. Estimates for child labour vary. It ranges between 250 and 304 million, if children aged 5–17 involved in any economic activity are counted. If light occasional work is excluded, ILO estimates there were 153 million child labourers aged 5–14 worldwide in 2008. This is about 20 million less than ILO estimate for child labourers in 2004. Some 60 percent of the child labour was involved in agricultural activities such as farming, dairy, fisheries and forestry. Another 25% of child labourers were in service activities such as retail, hawking goods, restaurants, load and transfer of goods, storage, picking and recycling trash, polishing shoes, domestic help, and other services. The remaining 15% laboured in assembly and manufacturing in informal economy, home-based enterprises, factories, mines, packaging salt, operating machinery, and such operations.[49][50][51] Two out of three child workers work alongside their parents, in unpaid family work situations. Some children work as guides for tourists, sometimes combined with bringing in business for shops and restaurants. Child labour predominantly occurs in the rural areas (70%) and informal urban sector (26%).

Contrary to popular belief, most child labourers are employed by their parents rather than in manufacturing or formal economy. Children who work for pay or in-kind compensation are usually found in rural settings as opposed to urban centres. Less than 3% of child labour aged 5–14 across the world work outside their household, or away from their parents.[16]

Child labour accounts for 22% of the workforce in Asia, 32% in Africa, 17% in Latin America, 1% in the US, Canada, Europe and other wealthy nations.[52] The proportion of child labourers varies greatly among countries and even regions inside those countries. Africa has the highest percentage of children aged 5–17 employed as child labour, and a total of over 65 million. Asia, with its larger population, has the largest number of children employed as child labour at about 114 million. Latin America and the Caribbean region have lower overall population density, but at 14 million child labourers has high incidence rates too.[53]

Accurate present day child labour information is difficult to obtain because of disagreements between data sources as to what constitutes child labour. In some countries, government policy contributes to this difficulty. For example, the overall extent of child labour in China is unclear due to the government categorizing child labour data as "highly secret".[54] China has enacted regulations to prevent child labour; still, the practice of child labour is reported to be a persistent problem within China, generally in agriculture and low-skill service sectors as well as small workshops and manufacturing enterprises.[55][56]

In 2014, the U.S. Department of Labor issued a List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, where China was attributed 12 goods the majority of which were produced by both underage children and indentured labourers.[57] The report listed electronics, garments, toys, and coal, among other goods.

The Maplecroft Child Labour Index 2012 survey[58] reports that 76 countries pose extreme child labour complicity risks for companies operating worldwide. The ten highest risk countries in 2012, ranked in decreasing order, were: Myanmar, North Korea, Somalia, Sudan, DR Congo, Zimbabwe, Afghanistan, Burundi, Pakistan and Ethiopia. Of the major growth economies, Maplecroft ranked Philippines 25th riskiest, India 27th, China 36th, Vietnam 37th, Indonesia 46th, and Brazil 54th, all of them rated to involve extreme risks of child labour uncertainties, to corporations seeking to invest in developing world and import products from emerging markets.

المسببات

المطلب الأول: دواعي التشغيل : إن إمعان النظر في دواعي عمل الطفل يقودنا إلى أخذ جولة عابرة حول بيئات متعددة من دول العالم التي تنتشر فيها تلك الظاهرة وتشكل حـدثا ً ملحوظـا ً وهاجـسا ً مقلقـا ً للمهتمين بهذا الشأن، ونجد أن لكل بيئة محلية دواعيها الخاصة بها والتي تختلف عـن البيئات الأخرى ولكن في المجمل هناك قواسم مشتركة يستطيع المتأمـل إدراكهـا والوقـوف عليها لتشكل بمجملها عوامل ودواعي كانت وراء بروز هذه الظاهرة في تلـك المجتمعـات، وأهم ماله صلة بموضوع البحث يمكن إيجازه في العوامل التالية :

أولاً: العامل الاقتصادي :

يعد العامل الاقتصادي من أهم العوامل التي تقف وراء تشغيل الأطفال ولهذا العامل في

الحقيقة أكثر من سبب ولكن أهمها : الحروب – والكوارث الطبيعيـة – وتـشرد الوالـدين – والهجرة غير الشرعية وغيرها ، وكلها تتسبب في قلة ذات اليد والذي يعتبر العامل الرئيسي لعمالة الأطفال، والدافع لاستغلالهم بل ويستلزم ، وتترتب عليه نتائج متعددة تساهم في انتشار الظاهرة خاصة في الدول النامية حيث أن العائلات بحاجة ماسة إلى الدخل والـدعم الـذي يوفره عمل الأطفال ، ففي بعض الأحيان يكون أجر الطفـل بمثابـة المـصدر الوحيـد، أو الأساسي للدخل الذي يكفل إعالة الوالدين أو أحداهما ويوفر الاحتياجات الأساسية التي يعجـز الكبار عن توفيرها، خاصة الأطفال الذين يفقدون الوالد ويعيشون فـي كنـف أمهـاتهم مـن الأرامل والمطلقات وهذا أيضا بدوره يؤدي إلى زيادة معدلات البطالة بين البالغين وخاصة في الأعمـال والصناعات والحرف التي لا تتطلب تأهيلا ً محددا ً أو جهدا ً خاصا ً من قبل العامل.

ثانياً : العامل الثقافي :

إن ثقافة المجتمعات الخاصة بها تؤثر سلبا ً أو إيجابا ً في عمالة الأطفال فما يعد ممنوعا ً في مجتمع ما قد تراه مجتمعات أخرى أمرا ً مسموحا ً به بل قد تراه تلـك المجتمعـات شـيئا ً ضروريا ً من أساسيات العيش والحياة ولذا فقد يكون إنجاب عشرة أطفال مرغوبـا ً بالنـسبة للفلاح الذي ينظر إليهم باعتبارهم مصدرا ً اقتصاديا ً فلا يشكلون عليه أدنى عـبء حيـث ينخرطون في العمل من نعومة أظفارهم ، لأن الأسرة في المجتمعات الفقيرة لازالـت تقـوم على التعاون وتقسيم العمل بين أعضائها إذ إن الأسرة وحدة اقتصادية متضامنة يقـوم فيهـا الأب بإعالة زوجته وأبنائه وتقوم الأم بأعمال المنزل وقد تعمل الزوجة والأبناء وحدة متعاونة من الناحية الاقتصادية ويتم العمل بينهم بشكل متفق عليه حسب ظروف كل مجتمع وبتتبع بعض الإحصاءات الرسمية يلاحظ أن نسبة عمل الأطفـال فـي المجتمعـات الريفية أكثر من نسبتهم في المجتمعات الحضرية حيث أن حوالي ٥٢ مليون طفـل عامـل، حسبما قدر الجهاز المركزي للتعبئة العامة والإحصاء العدد الإجمالي للأطفال العاملين في فئة العمر ٦-١٢ سنة تبلغ نسبة الأطفال العاملين ٧١،١% منهم في مناطق ريفية و٣٨،٩% فـي مناطق حضرية وهذا يدل على أن ثقافة المجتمع لها دور كبير في انخراط الأطفـال فـي سوق العمل .

ثالثاً: العامل البيئي في البلدان النامية :

قد يكون هناك ارتباط بين عمل الأطفال وبين بيئـة العمـل خاصـة فـي القطـاعين الزراعي والصناعي، وكذا انخفاض أجور الأطفال وكفاءاتهم في أداء بعض الأعمـال، مثـل المشغولات الصناعية الدقيقة والأعمال المساعدة في الورش الصناعية، وأدى ذلك إلى تكالب أصحاب الأعمال على تشغيل الأطفال لكونهم أقل أجرا ً، وأكثر انقيـادا ً وطاعـة وخـضوعا ً لأصحاب العمل ، ومما لا شك فيه أن هذه الأمور تساهم بالفعل في إيجاد البيئة الاجتماعية والاقتصادية الميسرة لظهور ولدعم ظاهرة عمل الأطفال، إلا أنها في مجملهـا لا تعـدو أن تكون من عوامل الجذب، ولذا لوحظ أن الأسباب المنتجة لهذه الظاهرة والمؤدية إلى إحـداثها، إما أن تكون عوامل اقتصادية أو عوامل ثقافية، وهناك بعض الأسـباب المتـصلة بالجانـب التعليمي، وعلى وجه التحديد الفشل في التعليم، ويليه الرغبة في تعلم صنعة كبـديل للتعلـيم، ويلي هذين السببين رغبة الطفل في الحصول على مال ينفقه على متطلباته الشخصية . والمهم هنا الإشارة إلى أن عمالة الأطفال بأشكالها الموجودة حاليا ُ مع ما تشتمل عليـه من مخالفات صارخة تعتبر ظاهرة خطيرة، بل ويترتب عليها قضايا أخـرى أهمهـا قـضية الاستغلال بكل أشكاله، وإن الأمر ليدعو إلى رؤية شاملة ينبغي التـصدي لهـا مـن خـلال سياسات اجتماعية تهتم بمصالح الفئات الفقيرة في المجتمعات النامية لكي يتم القـضاء علـى عمالة الطفل المخالفة حتى يتمتع الطفل العامل بحقه في الحياة والتعليم واللعب والصحة البدنية والنفسية السليمة كغيره من غير العاملين

رابعاً : المفاسد المترتبة على عمل الطفل'

إن المشاهد اليوم هو اتجاه عمل الطفل إلى المسار الخاطئ حتى أصبح الأغلب ارتباط تشغيل الأطفال بالمخالفات الشرعية والقانونية مما يتسبب في جملة من المفاسد ، والتي حفزت الكثير من المهتمين بهذا الشأن لإطلاق النداءات المؤيدة لمنع تشغيل الأطفال بالكلية ، وذلك لمفاسـد كثيرة طغت على الموقف العام المشاهد على المستوى المحلي والدولي، ولعل من أهـم تلـك المشكلات تلك الآثار المترتبة على عمالة الأطفال في سن مبكرة والتي يمكن تلخيـصها فيمـا يلي :

أولا ً: المفاسد البدنية للطفل :

إن تعرض الأطفال للمخاطر أثناء وجودهم بالعمل يعوق نموهم، وذلك لأن الأطفـال أكثر تأثرا بهذه المخاطر في طور النمو وأكثر عرضة لها مما يؤثر على اخـتلال الوظـائف الحيوية ومعدل النمو وتوازن الأجهزة المختلفة في الجسم، ولأنهم أقل تحملا لمصاعب العمـل والضغوط النفيسة التي تصاحب العمل مع عدم تقديم رعاية صحية لهم عند إلحـاقهم بالعمـل لدى أرباب تلك الأعمال، ويجب على الحكومات أن ترعي هؤلاء الأطفال لأنهم سيـصبحون القوى العاملة المستقبلية، والملاحظ أن معظم الأحداث العاملين يعانون من سوء التغذيـة ممـا يؤدي إلى ضعف مقاومة الجسم للأمراض المختلفة

ثانيا: المفاسد النفسية :

تشغيل الأطفال السائد في العالم حاليا ً ينطوي على انتهاك لحقوق الطفل بـل وحقـوق الإنسان بشكل عام ، فالطفل من الفئات الأضعف التي يسهل استغلالها ، مما يسبب له "العديـد من الأمراض النفسية والصحية ، وذلك بسبب حرمانه من حقه في التعليم ، وحرمانـه مـن العيش بطفولة آمنة ، وحرمانه من النمو الصحي السليم من الناحية الجسدية والنفسية .

ثالثا: المفاسد التربوية :

التسرب المدرسي هو عامل من العوامل الأساسية لعمل الأطفال ويرجـع سـببه إلـى تعرض الأطفال للمعاملة السيئة أو للعقاب البدني من المدرسين ،أو لضعف المناهج الدراسـية التي لا تسعى لتنمية فكر الطفل وإبداعاته، وكذا لعدم توفير فرص عمل للخـريجين، وتـدني العائد الاقتصادي والاجتماعي من التعليم، بالإضافة إلى غياب البرامج والسياسات التي تساعد على الحلول . ولعل الباحث من خلال الصفحات الماضية أستطاع إيصال الفكرة حول المصالح والمفاسـد الناجمة عن عمل الأطفال وما يترتب على تلك المفاسد من آثار مقلقة للمجتمع الدولي.

خامساً : علاج الظاهرة

العلاج عبارة عن رد فعل أو استجابة نشطة مخطط لها و ذات هدف معين نحو فرد معين صاحب المشكلة ، فالمعالجة في الحقيقة لا تزيد عن كونها عملية إعادة تأهيل للطفل و متابعة صحيحة لمشكلاته بكافة جوانبها و مهما كانت أسبابها .

أولاً : وضع حد للفقر

يستحيل وضع حد لعمالة الطفل قبل القضاء على الفقر و ليس هناك شك في أن القطاعات الأشد فقراً و المحرومة هي المصدر الرئيسي للأغلبية الساحقة من الأطفال العاملين و هذا ما يقود إلى الاستنتاج الذي ينص على أن الفصل بين الفقر و عمالة الطفل أمر غبر ممكن و سواء كان الشخص المستفيد من عمالة الطفل الوالدين أو أي صاحب عمل فإنهم يتغاضون عن عنصر الاستغلال رغم أنهم يرون أن عمالة الطفل و الفقر متلازمان . لذلك يجب تقليص مساحة الفقر ، فالحد من الفقر عبر النمو الاقتصادي ، و خلق فرص عمل ، و التوزيع الأفضل للدخل ، و تغيير ملامح الاقتصاد العالمي ، و التخصيص الأفضل للموازنات الحكومية ، و التوجيه الأفضل للممتلكات الخاصة من شانها أن تقلل من مساحة الفقر و بالتالي تقليص عمالة الطفل للحد الأدنى .

ثانياً : تفعيل القرارات المتخذة في المؤتمرات الاقليمية

فلا بد من القضاء على عمل الأطفال المحفوف بالمخاطر بمعزل عن الإجراءات الأوسع التي تهدف إلى تقليص مساحة الفقر. فلقد بدأ حكومات العالم بالتحول لمعالجة هذه المسألة وفاء للالتزامات التي أخذتها على عاتقها بالمصادقة على اتفاقية حقوق الطفل . فقد اتفق وزراء العمل لدول حركة عدم الانحياز المجتمعين في نيودلهي على أن استغلال الطفل و حيثما جرت ممارسته إنما يشكل انتهاكا للمثل الأخلاقية .

ثالثاً : تفعيل دور المؤسسات الأهلية

فقد أنيط بها استكشاف السبل لابعاد مشاكل الأطفال عند ظروف العمل الخطرة و توفير البدائل لهم . و ستنجح هذه المؤسسات في ذلك لأنها أكثر قربا للطفل من غيرها و أكثر قدرة على الوصول إليهم و أكثر فاعلية في التأثير على سلوكهم بالوسائل غير الرسمية .

رابعاً : تضافر جميع الجهات المعنية

الطريق الوحيد لإحراز تقدم على طريق إنهاء عمالة الطفل تنحصر في قيام المستهلكين و الحكومات بممارسة ضغوط عبر فرض عقوبات و إجراءات المقاطعة . و من هذا الجانب يجب على الجميع التعاون و التكاتف من أجل القضاء على هذا الوباء الذي يلحق بالطفل و يؤثر على بناء المجتمع .

خامساً : المحاولة الجادة للقضاء على الجهل

إن بناء القدرة المعرفية للطفل و إثراء عقله بالمعارف الحديثة من شأنها أن تقي الطفل من الاستغلال الذي يتعرض له كما أنه مفتاح المستقبل الذي أصبح يرتكز على المعلومات و المعارف . فالقوانين الدستورية في جميع أنحاء العالم تنص على أن من حق الجميع التعلم. و لن يكون ذلك إلا بزيادة عدد المدارس و المعاهد و الصروح التعليمية عندها فقط يتاح التعليم لجميع الفئات في المجتمع . سادساً : التوعية من خلال وسائل الإعلام يجب استخدام مختلف قنوات الاتصال و الإعلام التقليدية و المعاصرة لنشر الوعي لدى الأسرة و المجتمع معا و لبيان أهمية الطفولة و ضرورة الاهتمام بقضاياها و بيان احتياجاتها و مشاكلها . و لا يخفى على أحد ما للإعلام من تأثير على الرأي العام فلزام علينا استثمار هذا التأثير من القضاء أو تقليص مساحة عمالة الطفل .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

In media

- Letitia Elizabeth Landon addresses this issue in scathing terms in her poem The Factory. (1835). 'Tis an accursed thing!—she writes.

- Oliver Twist, a novel by Charles Dickens that was later adapted into films and into a theater production.

- "The Little Match Girl", a short story by Hans Christian Andersen that was later adapted into films and other media.

See also

- Child abuse

- Child labour in Africa

- Child labour in Bangladesh

- Child labour in India

- Child migration

- Child prostitution

- Child work in indigenous American cultures

- Children in cocoa production

- Children's rights movement

- Concerned for Working Children

- Ethical consumerism

- History of childhood

- International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour, IPEC

- International Research on Working Children

- Kinder der Landstrasse, Switzerland

- Labour law

- Legal working age

- London matchgirls strike of 1888

- Newsboys strike of 1899, successful strike in New York

- Street children

- Sweatshop

- Trafficking of children

- World Day Against Child Labour

International conventions and other instruments:

Notes

- ^ Laura Del Col. "The Life of the Industrial Worker in Nineteenth-Century England". victorianweb.org.

- ^ "The Factory and Workshop Act, 1901". Br Med J. 2 (2139): 1871–2. 1901. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2139.1871. PMC 2507680. PMID 20759953.

- ^ Momen, Md Nurul (2020). "Child Labor: History, Process, and Consequences". No Poverty. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (1st ed.). Springer, Cham. pp. 1–8. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69625-6_30-1. ISBN 978-3-319-69625-6. S2CID 240602977.

- ^ "What is child labour?". International Labour Organization. 2012.

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةUN - ^ "International and national legislation - Child Labour". International Labour Organization. 2011.

- ^ "Labour laws - An Amish exception". The Economist. 5 February 2004.

- ^ Larsen, P.B. Indigenous and tribal children: assessing child labour and education challenges. International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour (IPEC), International Labour Office.

- ^ "Council Directive 94/33/EC of 22 June 1994 on child labour". EUR-Lex. 2008.

- ^ أ ب ت Prügl, Elisabeth (1999). The Global Construction of Gender - Home based work in Political Economy of 20th Century. Columbia University Press. pp. 25–31, 50–59. ISBN 978-0231115612.

- ^ Hugh Cunningham; Pier Paolo Viazzo, eds. (1996). Child Labour in Historical Perspective: 1800-1985 (PDF). UNICEF. ISBN 978-88-85401-27-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2015.

- ^ Hindman, Hugh (2009). The World of Child Labour. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1707-1.

- ^ أ ب "In the world's poorest countries, slightly more than 1 in 5 children are engaged in child labour". UNICEF. June 2023.

- ^ أ ب "UNICEF Data – Child Labour". UNICEF. 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ أ ب "Child Labour". The Economist. 20 December 2005.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةep05 - ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةilo2008a - ^ Norberg, Johan (2007), Världens välfärd (Stockholm: Government Offices of Sweden), p. 58

- ^ "To eliminate child labour, "attack it at its roots" UNICEF says". UNICEF. 2013.

- ^ أ ب ت Diamond, J., The World Before Yesterday

- ^ Thompson, E. P. (1968). The Making of the English Working Class. Penguin.[صفحة مطلوبة]

- ^ "UNICEF" (PDF).

- ^ Walker, Steven (2021-07-12). Children Forsaken (in الإنجليزية). Critical Publishing. ISBN 978-1-913453-84-8.

- ^ Laura Del Col, West Virginia University, "The Life of the Industrial Worker in Nineteenth-Century England"

- ^ Thompson, E. P. (1968). The Making of the English Working Class. Penguin. pp. 366–367.

- ^ Jane Humphries, Childhood And Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution (2010) p. 33

- ^ أ ب Barbara Daniels, "Poverty and Families in the Victorian Era"

- ^ Pal, Jadab Kumar; Chakraborty, Sonali; Tewari, Hare Ram; Chandra, Vinod (March 2016). "The working hours of unpaid child workers in the handloom industry in India". International Social Science Journal. 66 (219–220): 197–204. doi:10.1111/issj.12121. ISSN 0020-8701.

- ^ "Child Labour and the Division of Labour in the Early English Cotton Mills Archived 9 يناير 2006 at the Wayback Machine".

- ^ David Cody. "Child Labour". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 2010-03-21.

- ^ Forster 2006, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Douglas A. Galbi. Centre for History and Economics, King's College, Cambridge CB2 1ST.

- ^ In The Communist Manifesto, Part II: "Proletariats and Communists" and Capital, Volume I, Part III

- ^ Neocleous, Mark. "The Political Economy of the Dead: Marx's Vampires" (PDF).

- ^ Marx, Karl. "Inaugural Address of the International Working Men's Association" (1864).

- ^ Hugh Cunningham (1996). "Combating Child Labour: The British Experience". In Hugh Cunningham; Pier Paolo Viazzo (eds.). Child Labour in Historical Perspective: 1800-1985 (PDF). UNICEF. pp. 41–53. ISBN 978-88-85401-27-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2015.

- ^ Freedman, Russell; Hine, Lewis (1994). Kids at work: Lewis Hine and the crusade against child labour. New York: Clarion Books. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-0395587034.

- ^ "The Industrial Revolution". Web Institute for Teachers. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008.

- ^ "Photographs of Lewis Hine: Documentation of Child Labour". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- ^ "Virginia: Cigarette Rollers". userpages.umbc.edu.

- ^ Child Labour in the South: Essays and Links to photographs from the Lewis Hine Collection at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

- ^ Warren, L., Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography (Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, 2006), p. 699.

- ^ Freedman, Russell (1998). Kids at Work: Lewis Hine and the Crusade Against Child Labour. Sandpiper. ISBN 978-0395797266.

- ^ Miller, Frieda (1979). Miller, Frieda S. Papers, 1909-1973. Radcliff College. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Linda Lobao; Katherine Meyer (2001). "The Great Agricultural Transition: Crisis, Change, and Social Consequences of Twentieth Century US Farming". Annual Review of Sociology. 27: 103–124. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.103. JSTOR 2678616.

- ^ Friedmann, Harriet (1978). "World Market, State, and Family Farm: Social Bases of Household Production in the Era of Wage Labour". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 20 (4): 545–586. doi:10.1017/S001041750001255X. S2CID 153765098.

- ^ "Table 2.8, WDI 2005, The World Bank" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2013.

- ^ "Child Statistics". UNICEF DATA. Archived from the original on 30 June 2012.

- ^ Antelava, Natalia (24 August 2007). "Child labour in Kyrgyz coal mines". BBC News. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ^ Yacouba Diallo; Frank Hagemann; Alex Etienne; Yonca Gurbuzer; Farhad Mehran (2010). Global child labour developments: Measuring trends from 2004 to 2008. ILO. ISBN 978-92-2-123522-4.

- ^ "The State of the World's Children 1997". UNICEF. Retrieved 2007-04-15.

- ^ "Server Error" (PDF). info.worldbank.org.

- ^ Tackling child labour: From commitment to action. ILO. 2012. ISBN 978-92-2-126374-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Children's Rights: China". Law Library of Congress, United States. 2012.

- ^ Lepillez, Karine (2009). "The dark side of labour in China" (PDF).

- ^ "China: End Child Labour in State Schools". Human Rights Watch. 4 December 2007. Archived from the original on 11 January 2015.

- ^ "List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor". www.dol.gov.

- ^ "Conflict and economic downturn cause global increase in reported child labour violations – 40% of countries now rated 'extreme risk' by Maplecroft". Maplecroft. 1 May 2012.

المراجع

External links

- Child Labor, Child Bondage, Why Children Work

- Combating Child Labor — Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor

- A UNICEF web resource with tables of % children who work for a living, by country and gender

- Rare child labour photos from the U.S. Library of Congress

- History Place Photographs from 1908 to 1912

- International Research on Child Labour

- International Program on the Elimination of Child Labour International Labour Organization (UN)

- World Day Against Child Labour 12 June

- Concerned for Working Children An India-based non-profit organisation working towards elimination of child labour

- The OneWorld guide to child labour

- The State of the World's Children – a UNICEF study

- "United States Child Labour, 1908–1920: As Seen Through the Lens of Sociologist and Photographer Lewis W. Hine" (video)

- Child Labour in Chile, 1880–1950 download complete text, in spanish

- 12 to 12 community portal ILO sponsored website on the elimination of child labour

- The ILO Special Action Programme to combat Forced Labour (SAP-FL)