جامعة ستانفورد

جامعة ستانفورد، أو رسمياً جامعة ليلاند ستانفورد الابن،[13][14] هي جامعة أبحاث خاصة أمريكية في ستانفورد، كاليفورنيا. افتتحت في 1 أكتوبر1891، جامعة خاصة تقع في جنوب شرق سان فرانسيسكو بحوالي 37 ميلاً وشمال غرب سان خوسيه بحوالي 20 ميلاً في ولاية كاليفورنيا بالقرب من مدينة بالو ألتو. الحرم يفترش 8,180 فدان، وهو ما يضعه بين أكبر الجامعات في الولايات المتحدة، وينتظم فيها 17,000 طالب.[15] Stanford is widely considered to be one of the most prestigious universities in the world.[أ]

| Leland Stanford Junior University | |

| |

| الشعار | Die Luft der Freiheit weht (German)[1] |

|---|---|

| الشعار بالعربية | "The wind of freedom blows"[1] |

| النوع | Private research university |

| تأسست | 1891 |

| المؤسس | Leland and Jane Stanford |

| الارتباط الأكاديمي | |

| الوقف | $36.3 billion (2022)[4] |

| الميزانية | $8.2 billion (2022–23)[5] |

| الرئيس | Marc Tessier-Lavigne |

| Provost | Persis Drell |

| الطاقم الأكاديمي | 2,279[6] |

| الطاقم الاداري | 15,314[7] |

| الطلبة | 17,246 (Fall 2021)[8] |

| طلاب نحو البكالوريوس | 7,858 (Fall 2021)[8] |

| دارسون بعد التخرج | 9,388 (Fall 2021)[8] |

| الموقع | Stanford، California، United States 37°25′42″N 122°10′08″W / 37.4282293°N 122.1688576°W[9]Coordinates: 37°25′42″N 122°10′08″W / 37.4282293°N 122.1688576°W[9] |

| الحرم | Large suburban,[10] 8,180 acres (33.1 km2)[6] |

| Other campuses | |

| Newspaper | The Stanford Daily |

| الألوان | Cardinal red & White[11] |

| الكنية | Cardinal |

| جالب الحظ | Stanford Tree (unofficial – no official university mascot)[12] |

Sporting affiliations | |

| الموقع الإلكتروني | www |

| |

Stanford was founded in 1885 by Leland and Jane Stanford in memory of their only child, Leland Stanford Jr., who had died of typhoid fever at age 15 the previous year.[2] Leland Stanford was a U.S. senator and former governor of California who made his fortune as a railroad tycoon. The university admitted its first students on October 1, 1891,[2][3] as a coeducational and non-denominational institution. Stanford University struggled financially after the death of Leland Stanford in 1893 and again after much of the campus was damaged by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake.[16] Following World War II, provost of Stanford Frederick Terman inspired and supported faculty and graduates' entrepreneurialism to build a self-sufficient local industry, which would later be known as Silicon Valley.[17]

The university is organized around seven schools on the same campus: three schools consisting of 40 academic departments at the undergraduate level as well as four professional schools that focus on graduate programs in law, medicine, education, and business. The university also houses the public policy think tank, the Hoover Institution. Students compete in 36 varsity sports, and the university is one of two private institutions in the Division I FBS Pac-12 Conference. As of May 26, 2022, Stanford has won 131 NCAA team championships,[18] more than any other university, and was awarded the NACDA Directors' Cup for 25 consecutive years, beginning in 1994–1995.[19] In addition, by 2021, Stanford students and alumni had won at least 296 Olympic medals including 150 gold and 79 silver medals.[20]

As of April 2021, 85 Nobel laureates, 29 Turing Award laureates,[note 1] and 8 Fields Medalists have been affiliated with Stanford as students, alumni, faculty, or staff.[41] In addition, Stanford is particularly noted for its entrepreneurship and is one of the most successful universities in attracting funding for start-ups.[42][43][44][45][46] Stanford alumni have founded numerous companies, which combined produce more than $2.7 trillion in annual revenue and have created 5.4 million jobs as of 2011, roughly equivalent to the seventh largest economy in the world (اعتبارا من 2020[تحديث]).[47][48][49] Stanford is the alma mater of U.S. President Herbert Hoover, the current Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, 74 living billionaires, and 17 astronauts.[50] In academia, its alumni include the current president of Yale and the provosts of Harvard and Princeton. It is also one of the leading producers of Fulbright Scholars, Marshall Scholars, Rhodes Scholars, and members of the United States Congress.[51]

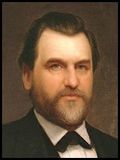

ليلاند ستانفورد مؤسس الجامعة |

من أفضل الجامعات بالعالم ـ توازي شهرتها جامعات معهد ماساتشوستس للتقنية و جامعة كمبريدج و جامعة هارفارد. وقد بدأ وادي السليكون منها بالستينات. ويسجل بالجامعة حوالي 6,700 طالب لدارسي البكالوريوس و 8,000 طالب للدراسات العليا كل سنة من الولايات المتحدة وجميع أنحاء العالم وهي جامعة كبرى بها أقسام متميزة بالفيزياء والأحياء والهندسة والطب والقانون والسياسة وعلم النفس.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التاريخ

Stanford University was founded in 1885 by Leland and Jane Stanford, dedicated to the memory of Leland Stanford Jr, their only child. The institution opened in 1891 on Stanford's previous Palo Alto farm.

Jane and Leland Stanford modeled their university after the great eastern universities, most specifically Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Stanford was referred to as the "Cornell of the West" in 1891 due to a majority of its faculty being former Cornell affiliates (professors, alumni, or both), including its first president, David Starr Jordan, and second president, John Casper Branner. Both Cornell and Stanford were among the first to make higher education accessible, non-sectarian, and open to women as well as men. Cornell is credited as one of the first American universities to adopt that radical departure from traditional education, and Stanford became an early adopter as well.[53]

From an architectural point of view, the Stanfords, particularly Jane, wanted their university to look different from the eastern ones, which had often sought to emulate the style of English university buildings. They specified in the founding grant[54] that the buildings should "be like the old adobe houses of the early Spanish days; they will be one-storied; they will have deep window seats and open fireplaces, and the roofs will be covered with the familiar dark red tiles". This guides the campus buildings to this day. The Stanfords also hired renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who previously designed the Cornell campus, to design the Stanford campus.

When Leland Stanford died in 1893, the continued existence of the university was in jeopardy due to a federal lawsuit against his estate, but Jane Stanford insisted the university remain in operation throughout the financial crisis.[55][56] The university suffered major damage from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake; most of the damage was repaired, but a new library and gymnasium were demolished, and some original features of Memorial Church and the Quad were never restored.[57]

During the early 20th century, the university added four professional graduate schools. Stanford University School of Medicine was established in 1908 when the university acquired Cooper Medical College in San Francisco;[58] it moved to the Stanford campus in 1959.[59] The university's law department, established as an undergraduate curriculum in 1893, was transitioned into a professional law school starting in 1908 and received accreditation from the American Bar Association in 1923.[60] The Stanford Graduate School of Education grew out of the Department of the History and Art of Education, one of the original 21 departments at Stanford, and became a professional graduate school in 1917.[61] The Stanford Graduate School of Business was founded in 1925 at the urging of then-trustee Herbert Hoover.[62] In 1919, The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace was started by Herbert Hoover to preserve artifacts related to World War I. The SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (originally named the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center), established in 1962, performs research in particle physics.[63]

In the 1940s and 1950s, an engineering professor and later provost Frederick Terman encouraged Stanford engineering graduates to invent products and start their own companies.[64] During the 1950s, he established Stanford Industrial Park, a high-tech commercial campus on university land.[65] Also in the 1950s William Shockley, co-inventor of the silicon transistor, recipient of the 1956 Nobel Prize for Physics, and later professor of physics at Stanford, moved to the Palo Alto area and founded a company, Shockley Semiconductor Laboratory. The next year eight of his employees resigned and formed a competing company, Fairchild Semiconductor. The presence of so many high-tech and semiconductor firms helped to establish Stanford and the mid-Peninsula as a hotbed of innovation, eventually named Silicon Valley after the key ingredient in transistors.[66] Shockley and Terman are often described, separately or jointly, as the "fathers of Silicon Valley".[67][68]

Stanford limited Jewish student admissions during the 1950s.[69]

Stanford in the 1960s rose from a regional university to one of the most prestigious in the United States, "when it appeared on lists of the "top ten" universities in America... This swift rise to performance [was] understood at the time as related directly to the university's defense contracts..."[70] Before the 1950s many regarded Stanford as being "a college for the children of wealthy parents".[71]

In the following decades, however, controversies would damage the reputation of the school. The 1971 Stanford prison experiment was criticized as unethical,[72] and the misuse of government funds from 1981 resulted in severe penalties to the school's research funding[73][74] and the resignation of Stanford President Donald Kennedy in 1992.[75]

الأرض

الحرم المركزي

The central academic campus is adjacent to Palo Alto, bounded by El Camino Real, Stanford Avenue, Junipero Serra Blvd, and Sand Hill Road. The United States Postal Service has assigned it two ZIP Codes: 94305 for campus mail and 94309 for P.O. box mail. It lies within area code 650.

الحرم غير المركزي

Stanford currently operates in various locations outside of its central campus.

On the founding grant:

- Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve is a 1,200-acre (490 ha) natural reserve south of the central campus owned by the university and used by wildlife biologists for research. Researchers and students are involved in biological research. Professors can teach the importance of biological research to the biological community. The primary goal is to understand the system of the natural Earth.[76]

- SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is a facility west of the central campus operated by the university for the Department of Energy. It contains the longest linear particle accelerator in the world, 2 miles (3.2 km) on 426 acres (172 ha) of land.[77]

Off the founding grant:

- Hopkins Marine Station, in Pacific Grove, California, is a marine biology research center owned by the university since 1892. Based on US Pacific Coast, it is one of the oldest marine laboratories. It includes 10 research laboratories and is also used for archaeological exploration purposes.[78] A graduate student of the anthropology department discover some broken elements, which leads to proof that 100 years before it was home to a Chinese American fishing village.[79]

- Study abroad locations: unlike typical study abroad programs, Stanford itself operates in several locations around the world; thus, each location has Stanford faculty-in-residence and staff in addition to students, creating a "mini-Stanford."[80]

- Redwood City campus for many of the university's administrative offices in Redwood City, California, a few miles north of the main campus. In 2005, the university purchased a small, 35-acre (14 ha) campus in Midpoint Technology Park intended for staff offices; development was delayed by The Great Recession.[81][82] In 2015 the university announced a development plan[83] and the Redwood City campus opened in March 2019.[84]

- The Bass Center in Washington, D.C. provides a base, including housing, for the Stanford in Washington program for undergraduates.[85] It includes a small art gallery open to the public.[86]

- China: Stanford Center at Peking University, housed in the Lee Jung Sen Building, is a small center for researchers and students in collaboration with Peking University.[87][88]

المعالم

Contemporary campus landmarks include the Main Quad and Memorial Church, the Cantor Center for Visual Arts and the Bing Concert Hall, the Stanford Mausoleum with the nearby Angel of Grief, Hoover Tower, the Rodin Sculpture Garden, the Papua New Guinea Sculpture Garden, the Arizona Cactus Garden, the Stanford University Arboretum, Green Library and the Dish. Frank Lloyd Wright's 1937 Hanna–Honeycomb House and the 1919 Lou Henry Hoover House are both listed on the National Register of Historic Places. White Memorial Fountain (also known as "The Claw") between the Stanford Bookstore and the Old Union is a popular place to meet and to engage in the Stanford custom of "fountain hopping"; it was installed in 1964 and designed by Aristides Demetrios after a national competition as a memorial for two brothers in the class of 1949, William N. White and John B. White II, one of whom died before graduating and one shortly after in 1952.[89][90][91][92]

Interior of the Stanford Memorial Church at the center of the Main Quad

Hoover Tower, at 285 feet (87 m), the tallest building on campus

The new (2006) Stanford Stadium, site of home football games

The Dish, a 150 feet (46 m) diameter radio telescope on the Stanford foothills overlooking the main campus

White Memorial Fountain (The Claw)

الإدارة والتنظيم

Stanford is a private, non-profit university administered as a corporate trust governed by a privately appointed board of trustees with a maximum membership of 38.[93][note 2] Trustees serve five-year terms (not more than two consecutive terms) and meet five times annually.[96] A new trustee is chosen by the current trustees by ballot.[94] The Stanford trustees also oversee the Stanford Research Park, the Stanford Shopping Center, the Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University Medical Center, and many associated medical facilities (including the Lucile Packard Children's Hospital).[97]

أمور أكاديمية

السمعة والترتيب

| ترتيب الجامعة | |

|---|---|

| على المستوى الوطني | |

| ARWU[98] | 2 |

| Forbes[99] | 2 |

| THE/WSJ[100] | 2 |

| U.S. News & World Report[101] | 3 |

| Washington Monthly[102] | 1 |

| على مستوى العالم | |

| ARWU[103] | 2 |

| QS[104] | 3 |

| التايمز[105] | 3 |

Slate in 2014 dubbed Stanford as "the Harvard of the 21st century".[107] In the same year The New York Times dubbed Harvard as the "Stanford of the East". In that article titled To Young Minds of Today, Harvard Is the Stanford of the East The New York Times concluded that "Stanford University has become America's 'it' school, by measures that Harvard once dominated."[108] In 2019, Stanford University took 1st place on Reuters' list of the World's Most Innovative Universities for the fifth consecutive year.[109] In 2022, Washington Monthly ranked Stanford at 1st position in their annual list of top universities in the United States.[110] In a 2022 survey by The Princeton Review, Stanford was ranked 1st among the top ten "dream colleges" of America, and was considered to be the ultimate "dream college" of both students and parents.[111][112] Stanford Graduate School of Business was ranked 1st in the list of America's best business schools by Bloomberg for 2022–23.[113][114] From polls of college applicants done by The Princeton Review, every year from 2013 to 2020 the most commonly named "dream college" for students was Stanford; separately, parents, too, most frequently named Stanford their ultimate "dream college."[115][116]

Globally Stanford is also ranked among the top universities in the world. The Academic Ranking of World Universities (ARWU) ranked Stanford second in the world (after Harvard) most years from 2003 to 2020.[117] Times Higher Education recognizes Stanford as one of the world's "six super brands" on its World Reputation Rankings, along with Berkeley, Cambridge, Harvard, MIT, and Oxford.[118][119]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الاكتشافات والإبداعات

العلوم الطبيعية

- Biological synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) – Arthur Kornberg synthesized DNA material and won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959 for his work at Stanford.

- First Transgenic organism – Stanley Cohen and Herbert Boyer were the first scientists to transplant genes from one living organism to another, a fundamental discovery for genetic engineering.[120][121] Thousands of products have been developed on the basis of their work, including human growth hormone and hepatitis B vaccine.

- Laser – Arthur Leonard Schawlow shared the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physics with Nicolaas Bloembergen and Kai Siegbahn for his work on lasers.[122][123]

- Nuclear magnetic resonance – Felix Bloch developed new methods for nuclear magnetic precision measurements, which are the underlying principles of the MRI.[124][125]

الحاسب والعلوم التطبيقية

- ARPANET – Stanford Research Institute, formerly part of Stanford but on a separate campus, was the site of one of the four original ARPANET nodes.[126][127]

- Internet—Stanford University was the site where the original design of the Internet was undertaken. Vint Cerf led a research group to elaborate the design of the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP/IP) that he originally co-created with Robert E. Kahn (Bob Kahn) in 1973 and which formed the basis for the architecture of the Internet.

- Frequency modulation synthesis – John Chowning of the Music department invented the FM music synthesis algorithm in 1967, and Stanford later licensed it to Yamaha Corporation.

- Google – Google began in January 1996 as a research project by Larry Page and Sergey Brin when they were both PhD students at Stanford.[128] They were working on the Stanford Digital Library Project (SDLP). The SDLP's goal was "to develop the enabling technologies for a single, integrated and universal digital library" and it was funded through the National Science Foundation, among other federal agencies.[129]

- Klystron tube – invented by the brothers Russell and Sigurd Varian at Stanford. Their prototype was completed and demonstrated successfully on August 30, 1937.[130] Upon publication in 1939, news of the klystron immediately influenced the work of U.S. and UK researchers working on radar equipment.

- RISC – ARPA funded VLSI project of microprocessor design. Stanford and UC Berkeley are most associated with the popularization of this concept. The Stanford MIPS would go on to be commercialized as the successful MIPS architecture, while Berkeley RISC gave its name to the entire concept, commercialized as the SPARC. Another success from this era were IBM's efforts that eventually led to the IBM POWER instruction set architecture, PowerPC, and Power ISA. As these projects matured, a wide variety of similar designs flourished in the late 1980s and especially the early 1990s, representing a major force in the Unix workstation market as well as embedded processors in laser printers, routers and similar products.[131]

- SUN workstation – Andy Bechtolsheim designed the SUN workstation for the Stanford University Network communications project as a personal CAD workstation,[132] which led to Sun Microsystems.

الأعمال وريادتها

Stanford is one of the most successful universities in creating companies and licensing its inventions to existing companies; it is often held up as a model for technology transfer.[42][43] Stanford's Office of Technology Licensing is responsible for commercializing university research, intellectual property, and university-developed projects.

The university is described as having a strong venture culture in which students are encouraged, and often funded, to launch their own companies.[44]

Companies founded by Stanford alumni generate more than $2.7 trillion in annual revenue, equivalent to the 10th-largest economy in the world.[48]

Some companies closely associated with Stanford and their connections include:

- Hewlett-Packard, 1939, co-founders William R. Hewlett (B.S, PhD) and David Packard (M.S).

- Silicon Graphics, 1981, co-founders James H. Clark (Associate Professor) and several of his grad students.

- Sun Microsystems, 1982, co-founders Vinod Khosla (M.B.A), Andy Bechtolsheim (PhD) and Scott McNealy (M.B.A).

- Cisco, 1984, founders Leonard Bosack (M.S) and Sandy Lerner (M.S) who were in charge of Stanford Computer Science and Graduate School of Business computer operations groups respectively when the hardware was developed.[133]

- Yahoo!, 1994, co-founders Jerry Yang (B.S, M.S) and David Filo (M.S).

- Google, 1998, co-founders Larry Page (M.S) and Sergey Brin (M.S).

- LinkedIn, 2002, co-founders Reid Hoffman (B.S), Konstantin Guericke (B.S, M.S), Eric Lee (B.S), and Alan Liu (B.S).

- Instagram, 2010, co-founders Kevin Systrom (B.S) and Mike Krieger (B.S).

- Snapchat, 2011, co-founders Evan Spiegel and Bobby Murphy (B.S).

- Coursera, 2012, co-founders Andrew Ng (Associate Professor) and Daphne Koller (Professor, PhD).

أشهر خريجيها

- فينت سيرف الذي يعرف بأب الإنترنت.

- مؤسسوا شركات جوجل و ياهو و يوتيوب و هوليت-باكارد و صن ميكروسيستمز و إنفيديا و سيسكو سيستمز وسيليكون غرافيكس و نايكي و غاب.

People

As of late 2016, Stanford had 2,153 tenure-line faculty, senior fellows, center fellows, and medical center faculty.[134]

Award laureates and scholars

Stanford's current community of scholars includes:

- 17 Nobel Prize laureates (as of October 2019, 83 affiliates in total);[134]

- 171 members of the National Academy of Sciences;[134]

- 109 members of National Academy of Engineering;[134]

- 76 members of National Academy of Medicine;[134]

- 288 members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences;[134]

- 19 recipients of the National Medal of Science;[134]

- 1 recipient of the National Medal of Technology;[134]

- 4 recipients of the National Humanities Medal;[134]

- 49 members of American Philosophical Society;[134]

- 56 fellows of the American Physics Society (since 1995);[135]

- 4 Pulitzer Prize winners;[134]

- 31 MacArthur Fellows;[134]

- 4 Wolf Foundation Prize winners;[134]

- 2 ACL Lifetime Achievement Award winners;[136]

- 14 AAAI fellows;[137]

- 2 Presidential Medal of Freedom winners.[134][138]

Stanford's faculty and former faculty includes 46 Nobel laureates,[134] 5 Fields Medalists, as well as 16 winners of the Turing Award, the so-called "Nobel Prize in computer science", comprising one third of the awards given in its 44-year history. The university has 27 ACM fellows. It is also affiliated with 4 Gödel Prize winners, 4 Knuth Prize recipients, 10 IJCAI Computers and Thought Award winners, and about 15 Grace Murray Hopper Award winners for their work in the foundations of computer science. Stanford alumni have started many companies and, according to Forbes, has produced the second highest number of billionaires of all universities.[139][140][141]

31st President of the United States Herbert Hoover (BA, 1895)

Former Associate Justice of the United States Sandra Day O'Connor (BA, 1950)

Venture capitalist billionaire Peter Thiel (BA, 1989; JD, 1992)

13 Stanford alumni have won the Nobel Prize.[142][143][144][145][146] As of 2019, 122 Stanford students or alumni have been named Rhodes Scholars.[147]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

انظر أيضاً

- List of universities by number of billionaire alumni

- List of colleges and universities in California

- S*, a collaboration between seven universities and the Karolinska Institute for training in bioinformatics and genomics

- Stanford School

ملاحظات

- ^ Undergraduate school alumni who received the Turing Award:

- Vint Cerf: BS Math Stanford 1965; MS CS UCLA 1970; PhD CS UCLA 1972.[21]

- Allen Newell: BS Physics Stanford 1949; PhD Carnegie Institute of Technology 1957.[22]

- Martin Hellman: BE New York University 1966, MS Stanford University 1967, Ph.D. Stanford University 1969, all in electrical engineering. Professor at Stanford 1971–1996.[23]

- John Hopcroft: BS Seattle University; MS EE Stanford 1962, Phd EE Stanford 1964.[24]

- Barbara Liskov: BSc Berkeley 1961; PhD Stanford.[25]

- Raj Reddy: BS from Guindy College of Engineering (Madras, India) 1958; M Tech, University of New South Wales 1960; Ph.D. Stanford 1966.[26]

- Ronald Rivest: BA Yale 1969; PhD Stanford 1974.[27]

- Robert Tarjan: BS Caltech 1969; MS Stanford 1971, PhD 1972.[28]

- Whitfield Diffie: BS Mathematics Massachusetts Institute of Technology 1965. Visiting scholar at Stanford from 2009–2010 and an affiliate from 2010–2012; currently, a consulting professor at CISAC (The Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University).[29]

- Doug Engelbart: BS EE Oregon State University 1948; MS EE Berkeley 1953; PhD Berkeley 1955. Researcher/Director at Stanford Research Institute (SRI) 1957–1977; Director (Bootstrap Project) at Stanford University 1989–1990.[30]

- Edward Feigenbaum: BS Carnegie Institute of Technology 1956, Ph.D. Carnegie Institute of Technology 1960. Associate Professor at Stanford 1965–1968; Professor at Stanford 1969–2000; Professor Emeritus at Stanford (2000–present).[31]

- Robert W. Floyd: BA 1953, BSc Physics, both from the University of Chicago. Professor at Stanford (1968–1994).[32]

- Sir Antony Hoare: Undergraduate at Oxford University. Visiting Professor at Stanford 1973.[33]

- Alan Kay: BA/BS from the University of Colorado at Boulder, Ph.D. 1969 from the University of Utah. Researcher at Stanford 1969–1971.[34]

- John McCarthy: BS Math, Caltech; PhD Princeton. Assistant Professor at Stanford 1953–1955; Professor at Stanford 1962–2011.[35]

- Robin Milner: BSc 1956 from Cambridge University. Researcher at Stanford University 1971–1972.[36]

- Amir Pnueli: BSc Math from Technion 1962, PhD Weizmann Institute of Science 1967. Instructor at Stanford 1967; Visitor at Stanford 1970[37]

- Dana Scott: BA Berkeley 1954, Ph.D. Princeton 1958. Associate Professor at Stanford 1963–1967.[38]

- Niklaus Wirth: BS Swiss Federal Institute of Technology 1959, MSC Universite Laval, Canada, 1960; Ph.D. Berkeley 1963. Assistant Professor at Stanford University 1963–1967.[39]

- Andrew Yao: BS physics National University of Taiwan 1967; AM Physics Harvard 1969; Ph.D. Physics, Harvard 1972; Ph.D. CS University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign 1975 Assistant Professor at Stanford University 1976–1981; Professor at Stanford University 1982–1986.[40]

- ^ The rules governing the board have changed over time. The original 24 trustees were appointed for life in 1885 by the Stanfords as were some of the subsequent replacements. In 1899 Jane Stanford changed the maximum number of trustees from 24 to 15 and set the term of office to 10 years. On June 1, 1903, she resigned her powers as founder and the board took on its full powers. In the 1950s, the board decided that its fifteen members were not sufficient to do all the work needed and in March 1954 petitioned the courts to raise the maximum number to 23, of whom 20 would be regular trustees serving 10-year terms and 3 would be alumni trustees serving 5-year terms. In 1970 another petition was successfully made to have the number raised to a maximum of 35 (with a minimum of 25), that all trustees would be regular trustees, and that the university president would be a trustee ex officio.[94] The last original trustee, Timothy Hopkins, died in 1936; the last life trustee, Joseph D. Grant (appointed in 1891), died in 1942.[95]

- ^

- "Rebecca S. Lowen. Creating the Cold War University: The Transformation of Stanford. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1997. Pp. xii, 316". The American Historical Review. 1998. doi:10.1086/ahr/103.5.1721. ISSN 1937-5239.

- Binder, Amy J.; Abel, Andrea R. (2019). "Symbolically Maintained Inequality: How Harvard and Stanford Students Construct Boundaries among Elite Universities". Sociology of Education (in الإنجليزية). 92 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1177/0038040718821073. ISSN 0038-0407. S2CID 150327748.

المراجع

- ^ أ ب Casper, Gerhard. "Die Luft der Freiheit weht—On and Off" (October 5, 1995).

- ^ أ ب ت "History: Stanford University". Stanford University. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ أ ب "Chapter 1: The University and the Faculty". Faculty Handbook. Stanford University. September 7, 2016. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "Stanford University reports return on investment portfolio, value of endowment". October 26, 2022. As of August 31, 2022.

- ^ "Finances – Facts 2020". May 6, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2020.

- ^ أ ب Communications, Stanford Office of University. "Introduction: Stanford University Facts". Stanford Facts at a Glance (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved January 22, 2022.

- ^ "Stanford Factbook 2021" (PDF). Stanford University. November 9, 2021. Retrieved January 22, 2022.

- ^ أ ب ت "Stanford Facts". Stanford University. Retrieved January 22, 2022.

- ^ "Stanford University". نظام معلومات الأسماء الجغرافية، المسح الجيولوجي الأمريكي. January 19, 1981.

- ^ "IPEDS-Stanford University". Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ "Color". Stanford Identity Toolkit. Stanford University. Retrieved January 16, 2022.

- ^ The Stanford Tree is the mascot of the band but not the university.

- ^ "'Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax – 2013' (IRS Form 990)" (PDF). foundationcenter.org (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 990s.foundationcenter.org. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ University, © Stanford; Stanford; California 94305. "The founding grant: with amendments, legislation, and court decrees". purl.stanford.edu (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved December 29, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Jones, Jennifer (November 21, 2019). "10 Largest College Campuses in the United States". Largest.org (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved July 8, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "History – Part 2 (The New Century): Stanford University". Stanford.edu. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ "History – Part 3 (The Rise of Silicon Valley): Stanford University". Stanford.edu. Archived from the original on December 20, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ Athletics, Stanford (May 24, 2022). "Simply Dominant". gostanford.com (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Stanford University. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Conference, Pac-12 (July 2, 2018). "Stanford wins 24th-consecutive Directors' Cup". Pac-12 News (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved June 1, 2019.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Athletics, Stanford (July 1, 2016). "Olympic Medal History". Stanford University Athletics (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ "Vinton Cerf – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Allen Newell". acm.org.

- ^ "Martin Hellman". acm.org.

- ^ "John E Hopcroft". acm.org.

- ^ "Barbara Liskov". acm.org.

- ^ "Raj Reddy – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Ronald L Rivest – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Robert E Tarjan – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Whitfield Diffie". acm.org.

- ^ "Douglas Engelbart". acm.org.

- ^ "Edward A Feigenbaum – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Robert W. Floyd – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ Lee, J.A.N. "Charles Antony Richard (Tony) Hoare". IEEE Computer Society. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- ^ "Alan Kay". acm.org.

- ^ "John McCarthy". acm.org.

- ^ "A J Milner – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Amir Pnueli". acm.org.

- ^ "Dana S Scott – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ "Niklaus E. Wirth". acm.org.

- ^ "Andrew C Yao – A.M. Turing Award Winner". acm.org.

- ^ Carey, Bjorn (August 12, 2014). "Stanford's Maryam Mirzakhani wins Fields Medal". Stanford Report (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Stanford University. Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- ^ أ ب Nigel Page. The Making of a Licensing Legend: Stanford University’s Office of Technology Licensing. Chapter 17.13 in Sharing the Art of IP Management. Globe White Page Ltd, London, U.K. 2007

- ^ أ ب Timothy Lenoir. Inventing the entrepreneurial university: Stanford and the co-evolution of Silicon Valley pp. 88-128 in Building Technology Transfer within Research Universities: An Entrepreneurial Approach Edited by Thomas J. Allen and Rory P. O'Shea. Cambridge University Press, 2014. ISBN 9781139046930

- ^ أ ب McBride, Sarah (December 12, 2014). "Special Report: At Stanford, venture capital reaches into the dorm". Reuters. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ Devaney, Tim (December 3, 2012). "One University To Rule Them All: Stanford Tops Startup List – ReadWrite". ReadWrite (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved April 6, 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "The University Entrepreneurship Report – Alumni of Top Universities Rake in $12.6 Billion Across 559 Deals". CB Insights Research (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). October 29, 2012. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Box". stanford.app.box.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ أ ب Silver, Caleb (March 18, 2020). "The Top 20 Economies in the World". Investopedia (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Investopedia. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Krieger, Lisa M. (October 24, 2012). "Stanford alumni's companies combined equal tenth largest economy on the planet". The Mercury News (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved April 6, 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Elkins, Kathleen (May 18, 2018). "More billionaires went to Harvard than to Stanford, MIT and Yale combined". cnbc (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved November 19, 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^

- "Top Producers". us.fulbrightonline.org. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- "Statistics". www.marshallscholarship.org. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "US Rhodes Scholars Over Time". www.rhodeshouse.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "Harvard, Stanford, Yale Graduate Most Members of Congress".

- ^ Davis, Margo; Nilan, Roxanne (November 1, 1989). The Stanford Album: A Photographic History, 1885–1945 (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1639-0.

- ^ Davis, Margo Baumgartner; Nilan, Roxanne (1989). The Stanford Album: A Photographic History, 1885–1945 (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Stanford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8047-1639-0.

- ^ "Founding Grant with Amendments" (PDF). November 11, 1885. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 7, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Edith R., Mirrielees (1959). Stanford: The Story of a University (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 82–91. LCCN 59013788.

- ^ Nilan, Roxanne (1979). "Jane Lathrop Stanford and the Domestication of Stanford University, 1893–1905". San Jose Studies (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 5 (1): 7–30.

- ^ "Post-destruction decisions". Stanford University and the 1906 Earthquake (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Stanford University School of Medicine and the Predecessor Schools: An Historical Perspective. Part IV: Cooper Medical College 1883-1912. Chapter 30. Consolidation with Stanford University 1906 - 1912". Stanford Medical History Center (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ "Stanford University School of Medicine and the Predecessor Schools: An Historical Perspective Part V. The Stanford Era 1909- Chapter 37. The New Stanford Medical Center Planning and Building 1953 - 1959". Stanford Medical History Center (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ "ABA-Approved Law Schools by Year". By Year Approved (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ "History". Stanford Graduate School of Education (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). September 17, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Our History". Stanford Graduate School of Business (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Stanford University". Encyclopedia Britannica. November 27, 2019.

- ^ Lécuyer, Christophe (August 24, 2007). Making Silicon Valley: Innovation and the Growth of High Tech, 1930-1970 (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية) (1st ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0262622110.

- ^ Sandelin, Jon. "Co-Evolution of Stanford University & the Silicon Valley: 1950 to Today" (PDF). WIPO (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Stanford University Office of Technology Licensing. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Gillmor, C. Stewart. Fred Terman at Stanford: Building a Discipline, a University, and Silicon Valley. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2004. Print.

- ^ Tajnai, Carolyn (May 1985). "Fred Terman, the Father of Silicon Valley". Stanford Computer Forum (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Carolyn Terman. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ^ Rosenberg, Scott (July 19, 2017). "Silicon Valley's First Founder Was Its Worst". Wired (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Stanford University apologizes for limiting Jewish student admissions during the 1950s

- ^ Lowen, Rebecca S. (July 1, 1997). Creating the Cold War University: The Transformation of Stanford (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية) (1st ed.). USA: University of California Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-520-91790-3.

- ^ Wallace, J. E. (July 3, 1985). "History scholar built stanford into top school" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). The Globe and Mail. ProQuest 1435607944. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ The Belmont Report, Office of the Secretary, Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects for Biomedical and Behavioral Research, April 18, 1979

- ^ "Stanford, government agree to settle a dispute over research costs". stanford.edu (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). News.stanford.edu. October 18, 1994. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Merl, Jean (July 30, 1991). "Stanford President, Beset by Controversies, Will Quit: Education: Donald Kennedy to step down next year. Research scandal, harassment charge plagued university". Los Angeles Times (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved May 16, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Folkenflik, David (November 20, 1994). "What Happened to Stanford's Expense Scandal?". Baltimore Sun (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Archived from the original on October 20, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ^ "About the Preserve". jrbp.stanford (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved May 1, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "About SLAC". slac.stanford.edu (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved April 4, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Howe, Kevin (May 10, 2011). "Pacific Grove". montereyherald.com (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved July 19, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Julian, Sam (August 17, 2010). "Graduate student uncovers Hopkins' immigrant history". news.stanford (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved May 3, 2022.

- ^ "Faculty-in-Residence : Bing Overseas Study Program". bosp.stanford.edu (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ^ Falk, Joshua (July 29, 2010). "Redwood City campus remains undeveloped" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). The Stanford Daily. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Chesley, Kate (September 10, 2013). "Redwood City approves Stanford office building proposals". Stanford Report. Stanford University. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ Kadvany, Elena (December 10, 2015). "Stanford's Redwood City campus moves closer to reality" (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Palo Alto Weekly. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ University, Stanford (January 31, 2020). "Stanford Redwood City campus evokes warmth of university". Stanford News (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "Bass Center Overview | Stanford in Washington". siw.stanford.edu. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ^ "The Art Gallery at Stanford in Washington | Stanford in Washington". siw.stanford.edu (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved September 19, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "About the Center". Stanford Center at Peking. Stanford University. Archived from the original on July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ "The Lee Jung Sen Building". Stanford Center at Peking University. Stanford University. Archived from the original on July 2, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2014.

- ^ Sullivan, Kathleen J. (August 5, 2010). "Machinists restoring White Memorial Fountain, aka The Claw, develop an affinity for the campus icon". Stanford News. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Sullivan, Kathleen J. (June 10, 2011). "Sculptor returns for update on White Plaza fountain makeover". Stanford News. Retrieved December 11, 2016.

- ^ Kofman, Nicole (May 22, 2012). "Frolicking in fountains". Stanford Daily (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Retrieved December 11, 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Steffen, Nancy L. (May 20, 1964). "The Claw: White Plaza Dedication". Stanford Daily. Retrieved December 11, 2016. Has information on the White brothers that slightly corrects some of the facts in other articles.

- ^ "Stanford Facts: Administration & Finances". facts.stanford.edu (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Stanford University. May 2, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ أ ب "Stanford University – The Founding Grant with Amendments, Legislation, and Court Decrees" (PDF). Stanford University. 1987. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ "Joseph D. Grant House – Parks and Recreation – County of Santa Clara". www.sccgov.org. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved October 30, 2019. Joseph D. Grant County Park (Santa Clara) is named for him.

- ^ "University Governance and Organization". bulletin.stanford.edu (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). Stanford University. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Stanford University Facts—Finances and Governance". Stanford University. Archived from the original on November 15, 2008. Retrieved November 27, 2008.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2020: National/Regional Rank". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2021". Forbes. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ "Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education College Rankings 2021". The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ "2021 Best National University Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "2020 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved August 31, 2020.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2015-United States". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "University Rankings". Quacquarelli Symonds Limited. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ^ "World University Rankings". THE Education Ltd. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "The World's Most Innovative Universities 2019". Reuters.

- ^ Oremus, Will (April 15, 2013). "Silicon Is the New Ivy". Slate. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ Pérez-Peña, Richard (May 29, 2014). "To Young Minds of Today, Harvard Is the Stanford of the East". The New York Times. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- ^ "The World's Most Innovative Universities 2019". Reuters.

- ^ "2022 National University Rankings".

- ^ "These are the country's 'dream' colleges, but price remains the top concern". CNBC.

- ^ "2022 College Hopes & Worries Press Release".

- ^ "Stanford, 1st in Bloomberg Businessweek's 2022–23 US B-School Rankings". Bloomberg.com.

- ^ "These Are the US's Best Business Schools". Bloomberg.com.

- ^ "College Hopes & Worries Press Release" (in الإنجليزية). Princeton Review. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ "2020 College Hopes & Worries Press Release". Princeton Review. March 17, 2020. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2022". Shanghai Ranking. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Baty, Phil (January 1, 1990). "Birds? Planes? No, colossal 'super-brands': Top Six Universities". Times Higher Education. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Ross, Duncan (May 10, 2016). "World University Rankings blog: how the 'university superbrands' compare". Times Higher Education. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ^ Yount, Lisa (2003). A to Z of biologists. New York: Facts on File. pp. 47–49. ISBN 978-0-8160-4541-9. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ^ Cohen, S. N. (September 16, 2013). "DNA cloning: A personal view after 40 years". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (39): 15521–15529. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11015521C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1313397110. PMC 3785787. PMID 24043817.

- ^ "Arthur L. Schawlow". IEEE Global History Network. IEEE. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ^ Hänsch, Theodor W. (December 1999). "Obituary: Arthur Leonard Schawlow". Physics Today. 52 (12): 75–76. Bibcode:1999PhT....52l..75H. doi:10.1063/1.2802854.

- ^ Alvarez, Luis W.; Bloch, F. (1940). "A Quantitative Determination of the Neutron Moment in Absolute Nuclear Magnetons". Physical Review. 57 (2): 111–122. Bibcode:1940PhRv...57..111A. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.57.111.

- ^ Bloch, F.; Hansen, W. W.; Packard, Martin (February 1, 1946). "Nuclear Induction". Physical Review. 69 (3–4): 127. Bibcode:1946PhRv...69..127B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.69.127.

- ^ "Network (SUNet — The Stanford University Network)". Stanford University Information Technology Services. July 16, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ "Stanford University". University Discoveries. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "Google Milestones". Google, Inc. Retrieved September 28, 2010.

- ^ The Stanford Integrated Digital Library Project, Award Abstract #9411306, September 1, 1994 through August 31, 1999 (Estimated), award amount $521,111,001

- ^ Varian, Dorothy. "The Inventor and the Pilot". Pacific Books, 1983 p. 187

- ^ Reilly, Edwin D. (2003). Milestones in Computer Science and Information Technology. p. 50. ISBN 1-57356-521-0.

- ^ Andreas Bechtolsheim; Forest Baskett; Vaughan Pratt (March 1982). "The SUN Workstation Architecture". Stanford University Computer systems Laboratory Technical Report No. 229. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ Duffy, Jim. "Critical milestones in Cisco history". Network World (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- ^ أ ب ت ث ج ح خ د ذ ر ز س ش ص ض "Stanford Facts: The Stanford Faculty". Stanford University. 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ "APS Fellows Archive". Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ "ACL Lifetime Achievement Award Recipients". Retrieved February 9, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Elected AAAI Fellows". Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ^ Levy, Dawn (July 22, 2003). "Edward Teller wins Presidential Medal of Freedom". Retrieved November 17, 2008.

Teller, 95, is the third Stanford scholar to be awarded a Presidential Medal of Freedom. The others are Nobel Prize-winning economist Milton Friedman (1988) and former Secretary of State George Shultz (1989).

- ^ Thibault, Marie (August 5, 2009). "Billionaire University". Forbes. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Pfeiffer, Eric W. (August 25, 1997). "What MIT Learned from Stanford". Forbes. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ "Stanford Entrepreneurs". Stanford University. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ "Alumni: Stanford University Facts". Stanford University. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ^ "Stanford Nobel Laureates". Stanford University. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- ^ "Alvin E. Roth – Biographical". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ^ "Richard E. Taylor – Biographical". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ^ "Press Release (Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2006)". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ^ "Undergraduate Profile: Stanford University Facts". Stanford Facts at a Glance (in الإنجليزية). Stanford Office of University Communications. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

للاستزادة

- Lee Altenberg, Beyond Capitalism: Leland Stanford's Forgotten Vision (Stanford Historical Society, 1990)

- Ronald N. Bracewell, Trees of Stanford and Environs (Stanford Historical Society, 2005)

- Ken Fenyo, The Stanford Daily 100 Years of Headlines (2003) ISBN 0-9743654-0-8

- Jean Fetter, Questions and Admissions: Reflections on 100,000 Admissions Decisions at Stanford (1997) ISBN 0-8047-3158-6

- Ricard Joncas, David Neumann, and Paul V. Turner. Stanford University. The Campus Guide. Princeton Architectural Press, 2006. Available online.

- Stuart W. Leslie, The Cold War and American Science: The Military-Industrial-Academic Complex at MIT and Stanford, Columbia University Press 1994

- Rebecca S. Lowen, R. S. Lowen, Creating the Cold War University: The Transformation of Stanford, University of California Press 1997

وصلات خارجية

- Official website

- Stanford Athletics website

- Texts on Wikisource:

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - "Leland Stanford Junior University". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "[[s:Collier's New Encyclopedia (1921)/{{{1}}}|{{{1}}}]]". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . دائرة المعارف البريطانية (eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.