نيقولاي يورگا

نيقولاي يورگا (Nicolae Iorga ؛ النطق بالرومانية: [nikoˈla.e ˈjorɡa]; sometimes Neculai Iorga, Nicolas Jorga, Nicolai Jorga or Nicola Jorga, born Nicu N. Iorga;[1] January 17, 1871 – November 27, 1940) was a Romanian historian, politician, literary critic, memoirist, poet and playwright. Co-founder (in 1910) of the Democratic Nationalist Party (PND), he served as a member of Parliament, President of the Deputies' Assembly and Senate, cabinet minister and briefly (1931–32) as Prime Minister. A child prodigy, polymath and polyglot, Iorga produced an unusually large body of scholarly works, consecrating his international reputation as a medievalist, Byzantinist, Latinist, Slavist, art historian and philosopher of history. Holding teaching positions at the University of Bucharest, the University of Paris and several other academic institutions, Iorga was founder of the International Congress of Byzantine Studies and the Institute of South-East European Studies (ISSEE). His activity also included the transformation of Vălenii de Munte town into a cultural and academic center.

| Nicolae Iorga | |

|---|---|

| |

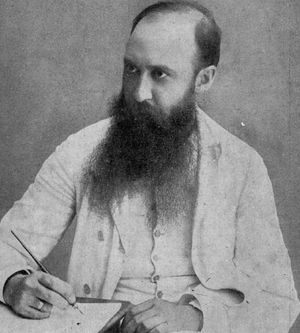

| Nicolae Iorga in 1914 (photograph published in Luceafărul) | |

| Prime Minister of Romania | |

| العاهل | Carol II |

| سبقه | Gheorghe Mironescu |

| خلفه | Alexandru Vaida-Voievod |

| تفاصيل شخصية | |

| وُلِد | يناير 17, 1871 Botoșani, Kingdom of Romania |

| توفي | نوفمبر 27, 1940 (aged 69) Strejnic, Kingdom of Romania |

| القومية | Romanian |

| الحزب | Democratic Nationalist Party |

| الزوج | Maria Tasu (div.) Ecaterina Bogdan |

| الدين | Romanian Orthodox |

| التوقيع | |

In parallel with his scientific contributions, Nicolae Iorga was a prominent right-of-center activist, whose political theory bridged conservatism, Romanian nationalism, and agrarianism. From Marxist beginnings, he switched sides and became a maverick disciple of the Junimea movement. Iorga later became a leadership figure at Sămănătorul, the influential literary magazine with populist leanings, and militated within the Cultural League for the Unity of All Romanians, founding vocally conservative publications such as Neamul Românesc, Drum Drept, Cuget Clar and Floarea Darurilor. His support for the cause of ethnic Romanians in Austria-Hungary made him a prominent figure in the pro-Entente camp by the time of World War I, and ensured him a special political role during the interwar existence of Greater Romania. Initiator of large-scale campaigns to defend Romanian culture in front of perceived threats, Iorga sparked most controversy with his antisemitic rhetoric, and was for long an associate of the far right ideologue A. C. Cuza. He was an adversary of the dominant National Liberals, later involved with the opposition Romanian National Party.

Late in his life, Iorga opposed the radically fascist Iron Guard, and, after much oscillation, came to endorse its rival King Carol II. Involved in a personal dispute with the Guard's leader Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, and indirectly contributing to his killing, Iorga was also a prominent figure in Carol's corporatist and authoritarian party, the National Renaissance Front. He remained an independent voice of opposition after the Guard inaugurated its own National Legionary dictatorship, but was ultimately assassinated by a Guardist commando.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

سيرته

طفولة عبقرية وتعسكر ماركسي

الدراسة في الخارج

نيقولاي يورگا من أكبر المؤرخين الرومانيين الذين كتبوا عن التاريخ الروماني والتاريخ العثماني، حيث وضع أكثر من كتاب عن التاريخ العثماني أكبرهم في 5 مجلدات كبار بعنوان "تاريخ الإمبراطورية العثمانية" تشمل تاريخ الدولة من بدايتها حتى عام 1912، ووضعه أولًا باللغة الألمانية وترجم لاحقًا للتركية بتقديم الراحل د.خليل إينالجيك حيث أثنى الدكتور خليل على الكتاب في تقريظه له، ووصفه بالمؤرخ الروماني الكبير الذي لا يعتمد على مصادر اعتيادية بل مصادر فريدة في كتابة التاريخ العثماني، كما تحدث عنه د. إلبير أورطةإيلي في كتابه العثمانيون في ثلاث قارات ووصفه أيضًا بصفات مشابهة.

Sămănătorul and 1906 riot

Neamul Românesc, Peasants' Revolt and Vălenii de Munte

يورگا وأزمة البلقان

ملجأ ياشي

خلق رومانيا الكبرى

International initiatives and American journey

رئيساً للوزراء

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

نزاعات أواسط ع1930

التقاعد في 1937 ومحاكمات كودريانو

اغتيال يورگا

The year 1940 saw the collapse of Carol II's regime. The unexpected cession of Bessarabia to the Soviets shocked Romanian society and greatly angered Iorga.[2][3] At the two sessions of the Crown Council held on June 27, he was one of six (out of 21) members to reject the Soviet ultimatum demanding Bessarabia's handover, instead calling vehemently for armed resistance.[2] Later, the Nazi-mediated Second Vienna Award made Northern Transylvania a part of Hungary. This loss sparked a political and moral crisis, eventually leading to the establishment of a National Legionary State with Ion Antonescu as Conducător and the Iron Guard as a governing political force. In the wake of this reshuffling, Iorga decided to close down his Neamul Românesc, explaining: "When a defeat is registered, the flag is not surrendered, but its fabric is wrapped around the heart. The heart of our struggle was the national cultural idea."[4] Perceived as Codreanu's murderer, he received renewed threats from the Iron Guard, including hate mail, attacks in the movement's press (Buna Vestire and Porunca Vremii)[5] and tirades from the Guardist section in Vălenii.[6] He further antagonized the new government by stating his attachment to the abdicated royal.[7]

Nicolae Iorga was forced out of Bucharest (where he owned a new home in Dorobanți quarter)[8] and Vălenii de Munte by the massive earthquake of November. He then moved to Sinaia, where he gave the finishing touches to his book Istoriologia umană ("Human Historiology").[9] He was kidnapped by a Guardist squad, the best-known member of which was agricultural engineer Traian Boeru,[10] on the afternoon of November 27, and killed in the vicinity of Strejnic (some distance from the city of Ploiești). He was shot at some nine times in all, with 7.65 mm and 6.35 mm handguns.[11] Iorga's killing is often mentioned in tandem with that of agrarian politician Virgil Madgearu, kidnapped and murdered by the Guardists on the same night, and with the Jilava Massacre (during which Carol II's administrative apparatus was decimated).[12] These acts of retribution, placed in connection with the discovery and reburial of Codreanu's remains, were carried out independently by the Guard, and enhanced tensions between it and Antonescu.[13]

Iorga's death caused much consternation among the general public, and was received with particular concern by the academic community. Forty-seven universities worldwide flew their flags at half-staff.[11] A funeral speech was delivered by the exiled French historian Henri Focillon, from New York City, calling Iorga "one of those legendary personalities planted, for eternity, in the soil of a country and the history of human intelligence."[11] At home, the Iron Guard banned all public mourning, excepting an obituary in Universul daily and a ceremony hosted by the Romanian Academy.[14] The final oration was delivered by philosopher Constantin Rădulescu-Motru, who noted, in terms akin to those used by Focillon, that the murdered scientist had stood for "our nation's intellectual prowess", "the full cleverness and originality of the Romanian genius".[15]

Iorga's remains were buried at Bellu, in Bucharest, on the same day as Madgearu's funeral—the attendants, who included some of the surviving interwar politicians and foreign diplomats, defied the Guard's ban with their presence.[16] Iorga's last texts, recovered by his young disciple G. Brătescu, were kept by literary critic Șerban Cioculescu and published at a later date.[17] Gheorghe Brătianu later took over Iorga's position at the South-East Europe Institute[18] and the Institute of World History (known as Nicolae Iorga Institute from 1941).[19]

نظرة سياسية

المحافظة والوطنية

معاداة السامية

جيوپوليتيكا

العمل العلمي

سمعة يورگا كعبقري

يورگا وبزوغ العرق الروماني

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

الدراسات البيزنطية والعثمانية

الناقد الثقافي

البدايات

العمل الأدبي

ذكراه

الهامش

- ^ Iova, p. xxvii.

- ^ أ ب خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةihstere2 - ^ Brătescu, p. 77

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةivliv - ^ Ornea (1995), p. 335. See also Iova, p. liii

- ^ Brătescu, p. 79

- ^ Neubauer, p. 164

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةapbucurestii - ^ Iova, p. lv. See also Brătescu, pp. 81, 84; Nastasă (2007), p. 126

- ^ Veiga, p. 310

- ^ أ ب ت Iova, p. lv

- ^ Brătescu, p. 82; Crampton, p. 118; Deletant, pp. 60–61; Ornea (1995), pp. 19, 196, 209–210, 339–341, 347, 357; Veiga, pp. 292–295, 309–310; Seton-Watson, pp. 214–215

- ^ Deletant, pp. 60–61; Ornea (1995), pp. 339–343

- ^ Iova, pp. lv–lvi. See also Ornea (1995), pp. 340–341

- ^ Iova, pp. lv–lvi

- ^ Brătescu, p. 82

- ^ Brătescu, p. 83

- ^ Nastasă (2007), p. 49

- ^ خطأ استشهاد: وسم

<ref>غير صحيح؛ لا نص تم توفيره للمراجع المسماةso&gh64

References

- Nation and National Ideology. Past, Present and Prospects. Proceedings of the International Symposium Held at the New Europe College, Center for the Study of the Imaginary & New Europe College, Bucharest, 2002, pp. 117–121. ISBN 973-98624-9-7; See:

- Irina Livezeanu, "After the Great Union: Generational Tensions, Intellectuals, Modernism, and Ethnicity in Interwar Romania", pp. 110–127

- Sorin Alexandrescu, "Towards a Modern Theory of Romanian Nationalism in the Interwar Period", pp. 138–164

- Paul Blokker, "Romania at the Intersection of Different Europes: Implications of a Pluri-civilizational Encounter", in Johann P. Arnason, Natalie J. Doyle, Domains and Divisions of European History, Liverpool University Press, Liverpool, 2010, pp. 161–180. ISBN 978-1-84631-214-4

- Lucian Boia,

- Istorie și mit în conștiința românească, Humanitas, Bucharest, 2000. ISBN 973-50-0055-5

- "Germanofilii". Elita intelectuală românească în anii Primului Război Mondial, Humanitas, Bucharest, 2010. ISBN 978-973-50-2635-6

- (بالفرنسية) Ioana Both, " 'Mihai Eminescu – Poète National Roumain.' Histoire et Anatomie d'un Mythe Culturel", in The New Europe College Yearbook 1997-1998, New Europe College, Bucharest, 2000, pp. 9–70. ISBN 973-98624-5-4

- G. Brătescu, Ce-a fost să fie. Notații autobiografice, Humanitas, Bucharest, 2003. ISBN 973-50-0425-9

- (Romanian) Lucian T. Butaru, Rasism românesc. Componenta rasială a discursului antisemit din România, până la Al Doilea Război Mondial, Editura Fundației pentru Studii Europene, Cluj-Napoca, 2010. ISBN 978-606-526-051-1

- George Călinescu, Istoria literaturii române de la origini pînă în prezent, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1986

- Paul Cernat, Avangarda românească și complexul periferiei: primul val, Cartea Românească, Bucharest, 2007. ISBN 978-973-23-1911-6

- George Ciprian, Mascărici și mîzgălici. Amintiri, Editura de stat pentru literatură și artă, Bucharest, 1958. OCLC 7288521

- Marcel Cornis-Pope, John Neubauer (eds.), History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe, Vol. II, John Benjamins, Amsterdam & Philadelphia, 2004. ISBN 90-272-3453-1; See:

- Monica Spiridon, "On the Borders of Mighty Empires: Bucharest, City of Merging Paradigms", pp. 93–105

- John Neubauer, Marcel Cornis-Pope, Sándor Kibédi-Varga, Nicolae Harsanyi, "Transylvania's Literary Cultures: Rivalry and Interaction", pp. 245–283

- R. J. Crampton, Eastern Europe in the Twentieth Century – and after, Routledge, London, 1997. ISBN 0-415-16423-0

- Ovid Crohmălniceanu, Literatura română între cele două războaie mondiale, Vol. I, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1972. OCLC 490001217

- Mihaela Czobor-Lupp, "The Tension between Philosophy, History and Politics in Forging the Meaning of Civil Society in Romanian Philosophical Culture", in Magdalena Dumitrana (ed.), Romania: Cultural Identity and Education for Civil Society. Romanian Philosophical Studies, V. Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change, Series IVA, Eastern and Central Europe, Volume 24, Council for Research in Values and Philosophy, Washington, 2004, pp. 91–134. ISBN 1-56518-209-X

- Dennis Deletant, Hitler's Forgotten Ally: Ion Antonescu and His Regime, Romania, 1940-1944, Palgrave Macmillan, London, 2006. ISBN 1-4039-9341-6

- Neagu Djuvara, Între Orient și Occident. Țările române la începutul epocii moderne, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995. ISBN 973-28-0523-4

- Vasile Drăguț, Vasile Florea, Dan Grigorescu, Marin Mihalache, Pictura românească în imagini, Editura Meridiane, Bucharest, 1970. OCLC 5717220

- Dan Grigorescu, Istoria unei generații pierdute: expresioniștii, Editura Eminescu, Bucharest, 1980. OCLC 7463753

- Francesco Guida, "Federal Projects in Interwar Romania: An Overvaulting Ambition?", in Marta Petricioli, Donatella Cherubini (eds.), For Peace in Europe: Institutions and Civil Society between the World Wars, Peter Lang AG, Brussels, 2007, pp. 229–257. ISBN 978-90-5201-364-0

- Victor Iova, "Tabel cronologic", in N. Iorga, Istoria lui Mihai Viteazul, Vol. I, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1979, pp. xxvii–lvi. OCLC 6422662

- Traian D. Lazăr, "O parte a 'clanului Iorga' ", in Magazin Istoric, June 2011, pp. 41–44

- Lucian Nastasă,

- Intelectualii și promovarea socială (pentru o morfologie a câmpului universitar), Editura Nereamia Napocae, Cluj-Napoca, 2003

- "Suveranii" universităților românești. Mecanisme de selecție și promovare a elitei intelectuale, Vol. I, Editura Limes, Cluj-Napoca, 2007. ISBN 978-973-726-278-3

- John Neubauer, "Conflicts and Cooperation between the Romanian, Hungarian, and Saxon Literary Elites in Transylvania, 1850–1945", in Victor Karady, Borbála Zsuzsanna Török (eds.), Cultural Dimensions of Elite Formation in Transylvania (1770–1950), Ethnocultural Diversity Resource Center, Cluj-Napoca, 2008, p. 159–185. ISBN 978-973-86239-6-5

- Stejărel Olaru, Georg Herbstritt (eds.), Vademekum Contemporary History Romania. A Guide through Archives, Research Institutions, Libraries, Societies, Museums and Memorial Places, Romanian Institute for Recent History, Stiftung für Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur, Berlin & Bucharest, 2004

- William O. Oldson, A Providential Anti-Semitism. Nationalism and Polity in Nineteenth-Century Romania, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 1991. ISBN 0-87169-193-0

- Z. Ornea,

- Anii treizeci. Extrema dreaptă românească, Editura Fundației Culturale Române, Bucharest, 1995. ISBN 973-9155-43-X

- Junimea și junimismul, Vol. II, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1998. ISBN 973-21-0562-3

- Ovidiu Pecican, Regionalism românesc. Organizare prestatală și stat la nordul Dunării în perioada medivală și modernă, Editura Curtea Veche, Bucharest, 2009. ISBN 978-973-669-631-2

- Sorin Radu, "Semnele electorale ale partidelor politice în perioada interbelică", in the National Museum of the Union Apulum Yearbook, Vol. XXXIX, 2002, pp. 573–586

- (بالفرنسية) Mihai Sorin Rădulescu, "Sur l'aristocratie roumaine de l'entre-deux-guerres", in The New Europe College Yearbook 1996-1997, New Europe College, Bucharest, 2000, pp. 339–365. ISBN 973-98624-4-6

- Tom Sandqvist, Dada East. The Romanians of Cabaret Voltaire, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts & London, 2006. ISBN 0-262-19507-0

- Stefano Santoro, L'Italia e l'Europa orientale: diplomazia culturale e propaganda 1918-1943, FrancoAngeli, Milan, 2005. ISBN 88-464-6473-7

- Hugh Seton-Watson, Eastern Europe between the Wars, 1918-1941, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1945. OCLC 463173616

- Hugh Seton-Watson, Christopher Seton-Watson, The Making of a New Europe. R.W. Seton-Watson and the Last Years of Austria-Hungary, Methuen Publishing, London, 1981. ISBN 0-416-74730-2

- Kenneth Setton, The Papacy and the Levant, 1204-1571. Volume II: The Fifteenth Century, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 1997. ISBN 0-87169-127-2

- Ioan Stanomir,

- Spiritul conservator. De la Barbu Catargiu la Nicolae Iorga, Editura Curtea Veche, Bucharest, 2008. ISBN 978-973-669-521-6

- "Un pămînt numit România", in Paul Cernat, Angelo Mitchievici, Ioan Stanomir, Explorări în comunismul românesc, Polirom, Iași, 2008, pp. 261–328. ISBN 973-681-794-6

- Nicolae-Șerban Tanașoca, "Aperçus of the History of Balkan Romanity", in Răzvan Theodorescu, Leland Conley Barrows (eds.), Studies on Science and Culture. Politics and Culture in Southeastern Europe, UNESCO-CEPES, Bucharest, 2001, pp. 94–170. OCLC 61330237

- Maria Todorova, Imagining the Balkans, Oxford University Press, Oxford etc., 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-538786-5

- Petre Țurlea, "Vodă da, Iorga ba", in Magazin Istoric, February 2001, pp. 43–47

- Francisco Veiga, Istoria Gărzii de Fier, 1919–1941: Mistica ultranaționalismului, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1993. ISBN 973-28-0392-4

- Tudor Vianu, Scriitori români, Vols. I-III, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1970–1971. OCLC 7431692

- George Voicu, "The 'Judaisation' of the Enemy in the Romanian Political Culture at the Beginning of the 20th Century", in the Babeș-Bolyai University Studia Judaica, 2007, pp. 138–150

- Leon Volovici, Nationalist Ideology and Antisemitism. The Case of Romanian Intellectuals in the 1930s, Pergamon Press, Oxford etc., 1991. ISBN 0-08-041024-3

- (Romanian) Alexandru Zub, "Istoricul în fața duratei imediate: aportul ego-istoriei", in Istoria recentă în Europa. Obiecte de studiu, surse, metode etice ale studiului istoriei recente. Lucrările simpozionului internațional organizat de Colegiul Noua Europă, New Europe College, Bucharest, 2002, pp. 33–51. ISBN 973-85697-0-2

وصلات خارجية

- Works by or about نيقولاي يورگا at Internet Archive

- Translations from Iorga, in Plural Magazine (various issues): "Advice at Dark" (excerpt), "History of the Romanians - Before Decebalus", "Language as an Element of the Romanian Soul", "Museums: What They Are and What They Must Be. The Example of America", "Our Defense Abroad", "Reading The History of the Romanians", "The Cultural and Intellectual Life of Bucharest", "The Nationalist Doctrine" (excerpts), "The Place of the Romanian People in Universal History", "Towards Sulina", "What I Understand by a Capital"

- (Romanian) The Nicolae Iorga Institute

- (Romanian) Revista Istorică, Editura Academiei entry

قالب:Chairman Senate Romania قالب:President Chamber of Deputies Romania قالب:RomanianInteriorMinisters قالب:Iorga Cabinet