ثورة القرنفل

ثورة القرنفل (برتغالية: Revolução dos Cravos؛ إنگليزية: Carnation Revolution؛ في 25 أبريل 1974) كانت إنقلاب عسكري الأبيض ذو ميول يسارية قضى على الدكتاتورية الفاشية. نظم الثورة رائد في الجيش بمساعدة ثلثمائة ضابط معظمهم برتبة نقيب. ورغم مناشدة الضباط الأهالي ان يلازموا منازلهم فقد خرجت جموع غفيرة الى الشوارع وقدمت الى الجنود السجائر واللبن والطعام. كان ذلك في موسم تفتح القرنفل. فوضعت احدى نساء لشبونة زهرة قرنفل في ماسورة بندقية أحد الجنود. واقتدى بها الآخرون وأخذوا يقدمون أزهار القرنفل الى باقي الجنود.

| ثورة القرنفل | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| جزء من the Portuguese transition to democracy and the Cold War | |||

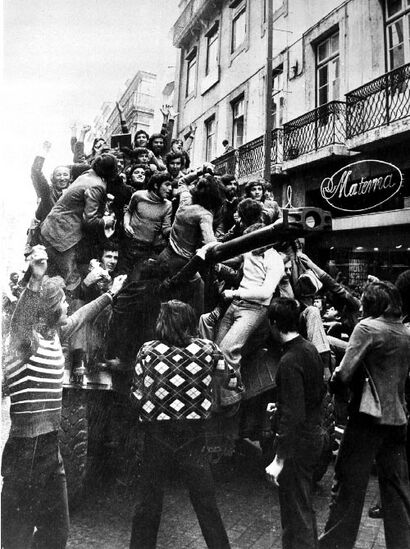

A crowd celebrates on a Panhard EBR armoured car in Lisbon, 25 April 1974. | |||

| التاريخ | 25 أبريل 1974 | ||

| المكان | Portugal | ||

| السبب |

| ||

| الطرق | Coup d'état | ||

| أسفرت عن | Coup successful

| ||

| أطراف الصراع الأهلي | |||

| الشخصيات الرئيسية | |||

| الضحايا والخسائر | |||

| 5 deaths[1] | |||

بدأت الثورة القرنفيلية بعد خمس وعشرين دقيقة من منتصف ليلة الخميس 25 أبريل 1974 في لشبونة حين قامت الإذاعة ببث أغنية مدينة البحر وكانت هذه الأغنية بمثابة إشارة انطلاق للوحدات العسكرية حول لشبونة لتنفيذ خطة انقلاب عسكري وضعت بعناية على يد الخياط الشبان الذين قادوا حركة القوات البحرية، وتم الانقلاب بفعالية ونجاح بعد مقاومة ضعيفة فاحتلت الوحدات العسكرية مباني الوزارات والمحطات الإعلامية ومكتب البريد والمطارات والاتصالات الهاتفية، وفي الصباح احتشدت الجماهير في الطرقات لتحية الجنود، وفي المساء كان الديكتاتور المخلوع مارشيلو كايتانو قد استسلم للقادة العسكريين الجدد للبرتغال، ومن اليوم التالي لترحيله إلى منفاه. [2]

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

خلفية

By the 1970s, nearly a half-century of authoritarian rule weighed on Portugal.[3] The 28 May 1926 coup d'état implemented an authoritarian regime incorporating social Catholicism and integralism.[4][5] In 1933, the regime was renamed the Estado Novo (New State).[6] António de Oliveira Salazar served as Prime Minister until 1968.[7]

In sham elections the government candidate usually ran unopposed, while the opposition used the limited political freedoms allowed during the brief election period to protest, withdrawing their candidates before the election to deny the regime political legitimacy.

The Estado Novo's political police, the PIDE (Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado, later the DGS, Direcção-Geral de Segurança and originally the PVDE, Polícia de Vigilância e Defesa do Estado), persecuted opponents of the regime, who were often tortured, imprisoned or killed.[8]

In 1958, General Humberto Delgado, a former member of the regime, stood against the regime's presidential candidate, Américo Tomás, and refused to allow his name to be withdrawn. Tomás won the election amidst claims of widespread electoral fraud, and the Salazar government abandoned the practice of popularly electing the president and gave the task to the National Assembly.[9]

Portugal's Estado Novo government remained neutral in the second world war, and was initially tolerated by its NATO post-war partners due to its anti-communist stance.[10] As the Cold War developed, Western Bloc and Eastern Bloc states vied with each other in supporting guerrillas in the Portuguese colonies, leading to the 1961–1974 Portuguese Colonial War.[11]

Salazar had a stroke in 1968, and was replaced as prime minister by Marcelo Caetano, who adopted a slogan of "continuous evolution", suggesting reforms, such as a monthly pension to rural workers who had never contributed to Portugal's social security. Caetano's Primavera Marcelista (Marcelist Spring) included greater political tolerance and freedom of the press, and was seen as an opportunity for the opposition to gain concessions from the regime. In 1969, Caetano authorised the country's first democratic labour union movement since the 1920s. However, after the elections of 1969 and 1973, hard-liners in the government and the military pushed back against Caetano, with political repression against communists and anti-colonialists.[بحاجة لمصدر]

الأحوال الاقتصادية

The Estado Novo regime's economic policy encouraged the formation of large conglomerates. The regime maintained a policy of corporatism which resulted in the placement of much of the economy in the hands of conglomerates including those founded by the families of António Champalimaud (Banco Totta & Açores, Banco Pinto & Sotto Mayor, Secil, Cimpor), José Manuel de Mello (Companhia União Fabril), Américo Amorim (Corticeira Amorim) and the dos Santos family (Jerónimo Martins).[بحاجة لمصدر]

One of the largest was the Companhia União Fabril (CUF), with a wide range of interests including cement, petro and agro chemicals, textiles, beverages, naval and electrical engineering, insurance, banking, paper, tourism and mining, with branches, plants and projects throughout the Portuguese Empire.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Other medium-sized family companies specialised in textiles (such as those in Covilhã and the northwest), ceramics, porcelain, glass and crystal (such as those in Alcobaça, Caldas da Rainha and Marinha Grande), engineered wood (such as SONAE, near Porto), canned fish (Algarve and the northwest), fishing, food and beverages (liqueurs, beer and port wine), tourism (in Estoril, Cascais, Sintra and the Algarve) and agriculture (the Alentejo, known as the breadbasket of Portugal) by the early-1970s. Rural families engaged in agriculture and forestry.[بحاجة لمصدر]

Income from the colonies came from resource extraction, of oil, coffee, cotton, cashews, coconuts, timber, minerals (including diamonds), metals (such as iron and aluminium), bananas, citrus, tea, sisal, beer, cement, fish and other seafood, beef and textiles.[بحاجة لمصدر] Labour unions were subject to severe restrictions,[12] and minimum wage laws were not enforced. Starting in the 1960s, the outbreak of colonial wars in Africa set off significant social changes, among them the rapid incorporation of women into the labour market.

الحرب الاستعمارية

Independence movements began in the African colonies of Portuguese Mozambique, Portuguese Congo, Portuguese Angola, and Portuguese Guinea. The Salazar and Caetano regimes responded with diverting more and more of Portugal's budget to colonial administration and military expenditure, and the country became increasingly isolated from the rest of the world, facing increasing internal dissent, arms embargoes and other international sanctions.[13]

By the early-1970s, the Portuguese military was overstretched and there was no political solution in sight. Although the number of casualties was relatively small, the war had entered its second decade; Portugal faced criticism from the international community, and was becoming increasingly isolated. In 1973 the UN General Assembly passed a resolution calling for Portugal's immediate withdrawal from Guinea.[14] Atrocities such as the Wiriyamu Massacre undermined the war's popularity and the government's diplomatic position, although details of the massacre are still disputed.[13][15][16][17][18][19][20]

The war became unpopular in Portugal, and the country became increasingly polarised. Thousands of left-wing students and anti-war activists avoided conscription by emigrating illegally, primarily to France and the United States. Meanwhile three generations of right-wing militants in Portuguese schools were guided by a revolutionary nationalism partially influenced by European neo-fascism, and supported the Portuguese Empire and an authoritarian regime.[21]

The war had a profound impact on the country. The revolutionary Armed Forces Movement (MFA) began as an attempt to liberate Portugal from the Estado Novo regime and challenge new military laws which were coming into force.[22][23] The laws would reduce the military budget and reformulate the Portuguese military.[24] Younger military-academy graduates resented Caetano's programme of commissioning militia officers who completed a brief training course and had served in the colonies' defensive campaigns at the same rank as academy graduates.[14]

الأحداث

بدأت الثورة في البرتغال بقيام قطاعات غاضبة في الجيش البرتغالي بانقلاب عسكري. فقد أدت محاولة الحكومة الفاشية إبقاء سيطرتها على مستعمراتها في أفريقيا إلى دخولها حروب لم تستطع أن تحتملها وانتهت في الأغلب بهزيمة الجيش البرتغالي. هكذا وفي الساعات الأولى من يوم 25 أبريل 1974 كان واضحًا لأي شخص في البرتغال يستمع إلى الراديو أن شيئًا خطيرًا قد حدث. وكان إذاعة أغنية ممنوعة لأحد المطربين اليساريين الشعبيين علامة على الانقلاب الذي حدث. ولأغلب مواطني لشبونة كان أول شيء عرفوه هو الاستيقاظ ليجدوا القوات المسلحة والدبابات تسيطر على الشوارع الرئيسية. وبمجرد ما اتضح إلى أي جانب تنتمي القوات انفجرت الشوارع في حفلات صاخبة يعانق فيها الناس الجنود ويضعون الورود على أسلحتهم.[25] ولو سار الأمر على هوى الرأسماليين الكبار لتوقف الاحتفال عند هذا الحد. فقد أصبح الجنرال السابق أنطونيو دي سبينولا رئيسًا للبرتغال بهدف إحداث إصلاح سطحي للنظام القديم. وكان الأمر ليسير حسب المخطط إلا أن أمرًا واحدًا خرج عن الخطة أو الحسبان وهو تأثير هذا الانهيار المفاجئ للنظام الفاشي على الطبقة العاملة البرتغالية.

فبعد أسبوع واحد من الانقلاب العسكري، قام العمال بالاحتفال بعيد العمال بحرية لأول مرة. حيث طاف حوالي 100 ألف عامل شوارع لشبونة، رافعين الرايات الحمراء، كما خطبت القيادة اليسارية العائدة من المنفى في الجموع. لكن العمال كانوا غير مستعدين لانتظار هذه القيادات حتى تقوم بالإصلاح. فالعمال وقعوا تحت ظلم شديد لأكثر من نصف قرن وحان الوقت ليضربوا مطالبين بالتعويض عن هذا الغين والظلم. ولم تكن مجرد إضرابات من أجل الخبز والزبد بل كان مطلبها الرئيسي هو "التطهير" أي التخلص من المديرين الفاشيين والمخبرين والجواسيس الفاشيين.

في ذلك الحين كان الحزب الشيوعي البرتغالي هو المنظمة العمالية الرئيسية في البرتغال. وهو حزب كان يمتلك المقومات الصحيحة للقيادة. فقد كان يمثل العمود الفقري لأي معارضة حقيقية ضد النظام خلال الأربعين عامًا السابقة على الثورة ونما بشكل كبير خلال الأيام التالية على الانقلاب. ولكن للأسف كانت إستراتيجية هذا الحزب الضخم هي أي شيء ما عدا الإستراتيجية الثورية.

في هذا الإطار رغب الحزب في أن يثبت لسبينولا ولكبار رجال الأعمال أنه قادر على السيطرة على الطبقة العاملة. وعني ذلك حملة من أجل إنهاء الإضراب بل أن الحزب ادعى أن الفاشيين كانوا وراء إضراب الخبازين في لشبونة وأدانه في جريدته (على الرغم من أن الإضراب كان من أجل إقصاء المديرين الفاشيين!!). بل أن الحزب رحب بشدة بتدخل القوات المسلحة لإنهاء إضراب عمال البريد على الرغم من أن أغلبية لجنة الإضراب كانوا أما أعضاء في الحزب أو مؤيدين له!

في البداية بدا أن إستراتيجية الحزب الشيوعي في خفت وتقليل حدة الصراع قد نجحت، إلا أن إيقاع الصراع الطبقي كان يرتفع لا العكس. ارتبك بعض المناضلين المتأثرين بالحزب فلم يكونوا يعرفون ماذا يفعلون إلا أن آخرين كان لهم رد فعل سريع بالتحول ضده والبحث عن اتجاهات أكثر ثورية. فبدأت المجموعات على يسار الحزب الشيوعي تكتسب نفوذًا وتأثيرًا في أكثر الأماكن نضالية. وهو ما ظهر عندما وافق الحزب الشيوعي على قانون منع الإضراب في صيف 1974 حيث قام خمسة آلاف عامل من عمال السفن بتحدي حظر التظاهر وطافوا شوارع برشلونة.

وأدى تزايد عدد أصحاب المصانع الذين يغلقون مصانعهم أو يهددون بإغلاقها في محاولة لإخماد الحركة العمالية إلى أن يقوم العمال بالسيطرة على هذه المصانع وتشغيلها أو فرض إرادتهم على مديريها. وفي ربيع 1975 كانت هناك المئات من المصانع التي تدار بهذه الطريقة.

ورغم إدانة الحزب الشيوعي والنقابات العمالية للتظاهر والإضراب قام ألف من ممثلي العمال في فبراير 1975 بالدعوة لتنظيم مظاهرة في لشبونة اعتراضًا على تزايد البطالة وعلى تهديد أسطول حلف شمال الأطلنطي بالاقتراب من البرتغال لقيت تأييد أكثر من 40 ألف عامل من معظم مصانع منطقة لشبونة رافعين الرايات الحمراء. وبدأ العمال المأجورون في الريف – بالذات في المقاطعات الكبرى في الجنوب – في مصادرة الأراضي من أصحابها الأغنياء الذين كانوا يقمعون ويستغلون آبائهم منذ قرون.

وبينما كل هذا يحدث، بدأت الطبقة الحاكمة القديمة في تنظيم نفسها. وكانت هناك عدة محاولات انقلابية قادها الجناح اليميني والتي لو كللت بالنجاح لانتهت البلاد إلى حمامات دم لكن يقظة العمال ونضاليتهم وحدها وقفت دون نجاحها. ففي سبتمبر 1974 ألقى سبينولا خطبة دعا فيها الشعب للاستيقاظ ليدافعوا عن أنفسهم في مواجهة من أسماهم "السلطويين المتطرفين" الذين يحاربون في الظل. وبدأ في تنظيم مظاهرة لمن دعاهم الأغلبية الصامتة اليمين بينما كانت البنادق توزع على الفاشيين القدامى. ومرة أخرى أوقفت التعبئة الجماهيرية العمالية هذه المحاولة بل وأجبرت سبينولا على الاستقالة كرئيس وأن قرر أن يختار الوقت المناسب.

وفي مارس 1975 حاول سبينولا القيام بمحاولة انقلاب أكثر جدية. حيث قام الضباط من الجناح اليميني بالسيطرة على واحدة من أهم القواعد الجوية العسكرية وإرسال الطائرات الحربية والهليوكوبتر لقذف الثكنات التي تحمي الطريق الشمالي للشبونة. وقامت قوات أخرى بحصار الثكنات كإشارة لضباط الجناح اليميني في كل البلاد للسيطرة على مقاليد السلطة. إلا أن نيران هذه المحاولة ارتدت إليهم.

فبدلاً من أن يتراجع العمال نتيجة المحاولة الانقلابية ردوا باستعراض بطولي للقوة. فبمجرد إعلان راديو العمال عن المحاولة الهجومية قام العمال في لشبونة بغلق البنوك ومنع أي فرد من الدخول. وخلت المحلات والمكاتب بينما اندفع العمال للانضمام للمظاهرات ووضع المتاريس. وعند أهم المراكز الصناعية جنوب العاصمة كما تم تشغيل صفارات الحريق بالمصانع بشكل مستمر وإنشاء كمائن عمالية تقوم بوقف وتفتيش كل العربات قرب الثكنات التي تم قذفها. كما قام عمال التشييد بإقامة متاريس ضخمة بواسطة البلدوزرات وأطنان من الأسمنت. أيضًا ذهب ممثلو العمال للثكنات طالبن تسليح المزيد من العمال استعدادًا للقتال. وتم إغلاق الطريق الحدودي لإسبانيا وفي كويمبرا، شمال لشبونة، وضع العمال السيارات على مجرى الطائرات في المطار بعد أن شوهدت طائرة تحوم على ارتفاع منخفض فوق المكان. في الوقت نفسه، احتشدت شوارع لشبونة ولوبورتو والمدن أخرى بآلاف المتظاهرين. وفي بعض الوحدات العسكرية أبدى الجنود بشكل علني تعاطفهم مع العمال لدرجة أن بعض القوات التي أرسلت أساسًا لبدء الانقلاب تم كسبهم لأفكار العمال.

هكذا أعطت محاولة الانقلاب الأحداث دفعة قوية جديدة لليسار، فتحولت موجة احتلال المصانع إلى طوفان يغمر البرتغال. وفي حالات كثيرة حيث سيطر العمال ونشطاء الاتحادات العمالية على المصانع كان يعلن ببساطة أن المصانع قد تم تأميمها، وفي الجيش بدأت القواعد من الجنود بل وبعض الضباط يتساءلون عن دورهم في المجتمع. وأصبحت المنظمة العسكرية "الكوبكون"، والتي أنشئت أساسًا من أجل حفظ النظام، أكثر تعاطفًا الآن مع نشاط العمال المناضلين أكثر من تعاطفها مع الحزب الشيوعي.

هكذا نضجت الأشياء للانتقال لمجتمع يقوم على سلطة العمال الحقيقية. إلا أن هذا المزاج الثوري انكسر في نوفمبر 1975. فقد استخدمت السلطة محاولة انقلابية ضعيفة قام بها ضباط يساريون كذريعة لاستعادة "النظام" تحت قيادة الحزب الاشتراكي والذي شكل في وقت مبكر حكومة تضم اليمينيين وقد حصل في انتخابات المجلس التمثيلي (البرلمان) على أعلى الأصوات. وبدأ النظام يعود للقوات المسلحة، حيث تمت إقالة قيادات الجيش المتعاطفة مع حركة العمال وعلى رأسهم "أوتيلو دي كارفالو" رئيس "الكوبكون" وتم فرض النظام على القواعد من الجنود. وعلى النقيض من الماضي القريب لم تحدث تعبئة للعمال. فقد انتهت الثورة. ولكن ماذا حدث في الفترة ما بين انقلاب مارس 1975 ونوفمبر 1975 جعل الأشياء تتحول بهذا الشكل؟

كان تواجد الحزب الاشتراكي في وقت اندلاع الثورة غير ذي شأن، إلا أنه استطاع أن ينمو ويكسب نفوذ جماهيري نتيجة ضعف التيارات التي على يساره. وقد انضم هذا الحزب إلى كورس اليمين حول "الأهداف الديكتاتورية" للعمال وللحركة النضالية للجناح اليساري. ووصفت جريدة الحزب "الجمهورية" سيطرة العامل على أنها ديكتاتورية. ومن ناحية أخرى استمرت مناورات بيروقراطية الحزب الشيوعي محاولة أن تفرض سيطرتها على مستويات الدولة لكن هذه المحاولات باءت بالفشل، وظل الحزب يقف في مواجهة الحركة العمالية الجماهيرية.

وفي ظل هذه الأوضاع كانت الفرصة الوحيدة والحقيقية لتحويل المزاج الانتصاري للطبقة العاملة والذي بدأ في مارس 1975 إلى دعوة للسيطرة على السلطة هي أن تستند إلى يسار ثوري، وهو الفصيل الذي كان صغيرًا للغاية عند إسقاط الديكتاتورية الفاشية كحال كل القوى السياسية في البرتغال باستثناء الحزب الشيوعي. ومثلت معارضة الحزب الشيوعي لموجة الإضرابات فرصة ثمينة لا نظير لها لنمو هذا اليسار الثوري، حيث أصبحت صحفه الأسبوعية تباع بشكل واسع كما استطاع أن يكسب أعضاءًا في معظم المصانع الرئيسية في منطقة لشبونة كما كان قادرًا على تنظيم مظاهرات ضخمة على الرغم من معارضة الحزب الشيوعي لها.

لكن السياسات والاستراتيجيات التي تبناها هذا اليسار الثوري كانت تعاني من نواقص خطيرة. فقد كانت أفكاره ملوثة بالستالينية في كافة صورها. وأسوأ الأمثلة كان الماويين الذين انتهوا إلى نقد الحزب الشيوعي من وجهة نظر يمينية بينما كان المتبنون لأفكار جيفارا هم الأفضل في محاولاتهم لدفع الثورة إلى الأمام. لكنهم كانوا يرون أن نجاح الثورة يعتمد أساسًا على النضال المسلح أكثر من الاعتماد على بناء حركة عمالية جماهيرية. هذه الأفكار اكتسبت قوة جذب واضحة في إطار لعب العسكريين دورًا قياديًا في الثورة البرتغالية منذ بدايتها.

ورغم نجاح اليسار في بناء حركة قاعدية ضخمة بين صفوف الجنود الثوريين إلا أنه فشل في العمالية هي القوى الوحيدة القادرة على إيقاف تحطم تأثير الجناح اليساري في الجيش – هذه التعبئة التي لم تحدث أبدًا.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ما بعدها

إنهاء الإستعمار

قضايا اقتصادية

الذكرى

Construction of what is now called the 25 de Abril Bridge began on 5 November 1962. It opened on 6 August 1966 as the Salazar Bridge, named after Estado Novo leader António de Oliveira Salazar. Soon after the Carnation Revolution of 1974, the bridge was renamed the 25 de Abril Bridge to commemorate the revolution. Citizens who removed the large, brass "Salazar" sign from a main pillar of the bridge and painted a provisional "25 de Abril" in its place were recorded on film.

Many Portuguese streets and squares are named vinte e cinco de Abril (25 April), for the day of the revolution. The Portuguese Mint chose the 40th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution for its 2014 2 euro commemorative coin.[26]

يوم الحرية

Freedom Day (25 April) is a national holiday, with state-sponsored and spontaneous commemorations of the civil liberties and political freedoms achieved after the revolution.[بحاجة لمصدر] It commemorates the 25 April 1974 revolution and Portugal's first free elections on that date the following year.

أفلام

- Setúbal, ville rouge (France–Portugal 1975 documentary, b/w and colour, 16 mm, 93 minutes, by Daniel Edinger) – In October 1975 Setúbal, neighbourhood committees, factory committees, soldiers' committees and peasant cooperatives organise a central committee.[27]

- Cravos de Abril (April Carnations), 1976 documentary, b/w and colour, 16 mm, 28 minutes, by Ricardo Costa – Depicts the revolutionary events from 24 April to 1 May 1974, illustrated by the French cartoonist Siné.

- Scenes from the Class Struggle in Portugal – U.S.–Portugal 1977, 16 mm, b/w and colour, 85 minutes, directed by Robert Kramer

- A Hora da Liberdade (The Hour of Freedom), 1999 documentary, by Joana Pontes, pt (Emídio Rangel) and pt (Rodrigo de Sousa e Castro)

- Capitães de Abril (April Captains), a 2000 dramatic film by Maria de Medeiros about the Carnation Revolution

- 25 de Abril: uma Aventura para a Democracia (25th April: an Adventure for Democracy), 2000 documentary, by Edgar Pêra

- The BBC-made A New Sun is Born, a two-part television series, for the UK's Open University. The first episode details the coup, and the second narrates the transition to democracy.[28]

- Longwave (Les Grandes Ondes (à l'ouest)), a 2013 screwball comedy about Swiss radio reporters assigned to Portugal in 1974[29][30]

- The GDR made several films about the revolution and transmitted on state television, including, (Lourenço und der Lieutenant) and (Sta Vitoria gibt nicht auf).

- Revolução sem sangue (2024)

انظر أيضاً

الهامش

- ^ "25 de Abril: a revolução que não foi assim tão branda". Diário de Notícias.

- ^ لنثقف أنفسنا سياسيا: الانتقال الديمقراطي - التجربة البرتغالية

- ^ Sousa, Helena. "Recent Political History of Portugal". University of Beira Interior. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Pinto, António Costa and Rezola, Maria Inácia, 'Political Catholicism, Crisis of Democracy and Salazar's New State in Portugal', Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, 8:2, 353–368.

- ^ Pinto, António Costa; Rezola, Maria Inácia (2007). "Political Catholicism, Crisis of Democracy and Salazar's New State in Portugal". Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions (in الإنجليزية). 8 (2): 353–368. doi:10.1080/14690760701321320. ISSN 1469-0764. OCLC 4893762881. S2CID 143494119.

- ^ Williams, Emma Slattery (September 30, 2021). "Your guide to the Carnation Revolution". History Extra. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ "António de Oliveira Salazar: prime minister of Portugal". Encyclopædia Britannica. April 24, 2022. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Silva, Lara (April 25, 2022). "25 Things To Know About Portugal's Carnation Revolution". Portugal.com. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Oliveira, Pedro Aires (2011). "Generous Albion? Portuguese anti-Salazarists in the United Kingdom, c. 1960––74". Portuguese Studies. 27 (2): 175–207. doi:10.1353/port.2011.0005. ISSN 2222-4270. OCLC 9681167242.

- ^ "Portugal and NATO". NATO. Retrieved April 25, 2022.

- ^ Schliehe, Nils (2019-05-01). "West German Solidarity Movements and the Struggle for the Decolonization of Lusophone Africa". Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais (in الإنجليزية) (118): 173–194. doi:10.4000/rccs.8723. ISSN 0254-1106. OCLC 8514209518. S2CID 155462211.

- ^ "O movimento sindical durante o Estado Novo: estado actual da investigação" (PDF). Universidade do Porto.

- ^ أ ب "Adrian Hastings". The Daily Telegraph. London. 26 June 2001.

- ^ أ ب Matos, José Augusto; Oliveira, Zélia (October 2023). Carnation Revolution. Volume 1: The Road to the Coup that changed Portugal, 1974. Warwick: Helion & Co. Ltd. ISBN 9781804513668.

- ^ Gomes, Carlos de Matos, Afonso, Aniceto. Oa anos da Guerra Colonial – Wiriyamu, De Moçambique para o mundo. Lisboa, 2010.

- ^ Arslan Humbarachi & Nicole Muchnik, Portugal's African Wars, N.Y., 1974.

- ^ Cabrita, Felícia (2008). Massacres em África. A Esfera dos Livros, Lisbon. pp. 243–282. ISBN 978-989-626-089-7.

- ^ Westfall, William C., Jr., Major, United States Marine Corps, Mozambique-Insurgency Against Portugal, 1963–1975, 1984. Retrieved on 10 March 2007.

- ^ "Mozambique: Mystery Massacre". Time. 30 July 1973. Archived from the original on 18 September 2008.

- ^ "Portuguese Prime Minister (Visit)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard) (in الإنجليزية البريطانية). 10 July 1973. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- ^ A direita radical na Universidade de Coimbra (1945–1974) Archived 3 مارس 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Marchi, Riccardo. A direita radical na Universidade de Coimbra (1945–1974). Anál. Social, July 2008, nº 188, pp. 551–576. ISSN 0003-2573.

- ^ (in برتغالية) Movimento das Forças Armadas (MFA). In Infopédia [Em linha]. Porto: Porto Editora, 2003–2009. [Consult. 2009-01-07]. Disponível na www: URL: http://www.infopedia.pt/$movimento-das-forcas-armadas-(mfa).

- ^ Movimento das Forças Armadas (1974–1975), Projecto CRiPE – Centro de Estudos em Relações Internacionais, Ciência Política e Estratégia. © José Adelino Maltez. Cópias autorizadas, desde que indicada a origem. Última revisão em: 2 October 2008.

- ^ Decretos-Leis n.os 353, de 13 de Julho de 1973, e 409, de 20 de Agosto.

- ^ 25 عامًا على الثورة البرتغالية، مركز الدراسات الاشتراكية، مصر

- ^ "Commemorative coins". European Commission - European Commission (in الإنجليزية). Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- ^ "Setubal Ville Rouge". ISKRA. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ A New Sun Is Born (1997). OCLC 51658463.

- ^ Boyd van Hoeij (22 August 2013). "Longwave (Les Grandes Ondes (a l'Ouest)): Locarno Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ^ "Les grandes ondes (à l'ouest) (2013)". IMDb. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

وصلات خارجية

- Phil Mailer, "Portugal – The Impossible Revolution?" (All sixteen Chapters and the Introduction by Maurice Brinton)