اللغة المصرية

اللغة المصرية أو المصرية القديمة (r n km.t)[1][6]، هي فرع منقرض من اللغات الأفرو-آسيوية التي كانت تستخدم في مصر القديمة. اللغة المصرية هي لغة قديمة، وهي معروفة اليوم من خلال مجموعة كبيرة من مجمع النصوص، والتي أصبحت متاحة للعالم الحديث بعد فك رموز النصوص المصرية القديمة في أوائل القرن التاسع عشر. تعد اللغة المصرية واحدة من أقدم اللغات المكتوبة المعروفة، حيث تم تسجيلها لأول مرة في الكتابة الهيروغليفية في أواخر الألفية الرابعة ق.م.. كما تعتبر أطول لغة بشرية موثقة، حيث يمتد تاريخ كتابتها لأكثر من 4000 سنة.[7] يُعرف شكلها الكلاسيكي "بالمصرية الوسيطة. كانت هذه هي اللهجة العامية في الدولة الفرعونية الوسطى، وظلت اللغة الأدبية في مصر حتى العصر الروماني. وبحلول العصور القديمة الكلاسيكية، تطورت اللغة المنطوقة إلى الديموطية، وبحلول العصر الروماني، تنوعت إلى اللهجات القبطية. وبعد الفتح الإسلامي لمصر، حلت محلها اللغة العربية، على الرغم من أن القبطية البحيرية لا تزال مستخدمة كلغة شعائرية اللكنيسة القبطية.[8][note 2]

| اللغة المصرية | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

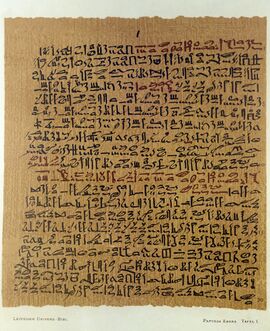

بردية إبرز تصف بشكل تفصيلي علاج الربو. | |||||||

| المنطقة | في الأصل، في جميع أنحاء مصر القديمة وأجزاء من النوبة (خاصة في عهد الممالك النوبية)[2] | ||||||

| العرق | قدماء المصريين | ||||||

| الحقبة | أواخر الألفية الرابعة ق.م. - القرن 19 الميلادي[note 2] (مع انقراض اللغة القبطية؛ لا تزال تستخدم كلغة شعائرية للكنيسة الأرثوذوكسية القبطية والكنيسة الكاثوليكية القبطية | ||||||

الأفرو-آسيوية

| |||||||

| اللهجات |

| ||||||

| الهيروغليفية، الهيروغليفية المخطوطة، الهيراطية، الديموطية والقبطية (لاحقًا، في بعض الأحيان، الأبجدية العربية في الترجمات الحكومية والأبجدية اللاتينية في الترجمة الصوتية وفي العديد من القواميس الهيروغليفية[5]) | |||||||

| أكواد اللغات | |||||||

| ISO 639-2 | egy (أيضاً cop للقبطية) | ||||||

| ISO 639-2 | egy (أيضاً cop للقبطية) | ||||||

| ISO 639-3 | egy (أيضاً cop للقبطية) | ||||||

| Glottolog | egyp1246 | ||||||

| Linguasphere | 11-AAA-a | ||||||

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التصنيف

اللغة المصرية هي إحدى فروع عائلة اللغات الأفرو-آسيوية.[9][10] من بين السمات النمطية للغة المصرية النموذجية الأفرو-آسيوية المتمثلة في الصرف الاشتقاقي، الصرف الغير متتابع، وسلسلة الحروف الصامتة الحلقية، ونظام الحروف الصائتة-الثلاثية /a i u/، اللاحقة الاسمية المؤنثة *-at، البادئة الاسمية m-، لاحقة الصفة -ī واللاحقات اللفظية الشخصية المميزة.[9] من بين الفروع الأفروآسيوية الأخرى، اقترح اللغويون بشكل مختلف أن اللغة المصرية تشترك في أوجه تشابه كبرى مع اللغة الأمازيغية[11] السامية[10][12][13] وخاصة العربية[بحاجة لمصدر] (المستخدمة في مصر حالياً) والعبرية.[10] ومع ذلك، فقد زعم علماء آخرون أن اللغة المصرية كانت تتمتع بروابط لغوية أوثق مع مناطق شمال شرق أفريقيا.[14][15][16]

هناك نظريتان تسعيان إلى تحديد المجموعات المتجانسة بين اللغة المصرية والأفرو-آسيوية، النظرية التقليدية ونظرية المقارنة الجديدة التي أسسها أوتو روسلر [السامية].[17] بحسب نظرية المقارنة الجديدة، في اللغة المصرية، الحروف الصامتة الصائتة الأفرو-آسيوية الأولية */d z ð/ تطورت إلى حروف حلقية ⟨ꜥ⟩ /ʕ/: بالمصرية ꜥr.t 'بوابة'، بالسامية dalt 'باب'. بدلاً من ذلك، تنازع النظرية التقليدية القيم المعطاة لتلك الحروف الصامتة من خلال نظرية المقارنة الجديدة، وبدلاً من ذلك تربط ⟨ꜥ⟩ بالحرف السامي /ʕ/ و/ɣ/.[18] تتفق المدرستان على أن الحرف الأفرو-آسيوية */l/ قد دُمج مع الحرف المصري ⟨n⟩، ⟨r⟩، ⟨ꜣ⟩، و⟨j⟩ باللهجة التي استندت إليها اللغة المكتوبة، لكنها ظلت محفوظة في اللهجات المصرية الأخرى. واتفقوا أيضاً على أن الحرف الأصلي */k g ḳ/ palatalise to ⟨ṯ j ḏ⟩ في بعض البيئات وحُفظ متمثلاً في الحرف ⟨k g q⟩ في بيئات أخرى.[19][20]

للغة المصرية جذور ثنائية وربما أحادية، على النقيض من تفضيل السامية للجذور الثلاثية. ربما تكون اللغة المصرية أكثر محافظة، ومن المرجح أن اللغة السامية خضعت لتعديلات لاحقة حولت الجذور إلى النمط ثلاثي الجذر.[21]

على الرغم من أن اللغة المصرية هي أقدم لغة أفرو-آسيوية موثقة في شكل مكتوب، فإن ذخيرتها الصرفية تختلف كثيرًا عن ذخيرة بقية اللغات الأفرو-آسيوية بشكل عام، واللغات السامية بشكل خاص. هناك عدة احتمالات: ربما كانت اللغة المصرية قد خضعت بالفعل لتغييرات جذرية من اللغة الأفرو-آسيوية الأولية قبل تسجيلها؛ أو ربما تمت دراسة عائلة اللغات الأفرو-آسيوية حتى الآن بنهج شبه مركزي مفرط؛ أو كما يقترح ج. تسرتلي، فإن اللغة الأفروآسيوية هي رابطة لغات متجانسة وليست مجموعة لغات متوارثة.[22]

التاريخ

يمكن تقسيم اللغة المصرية القديمة إلى المجموعات التالية:[23][24]

- المصرية

- المصرية المبكرة، المصرية الأقدم، أو المصرية الكلاسيكية

- المصرية القديمة

- المصرية المبكرة، المصرية القديمة المبكرة، المصرية القديمة العتيقة، المصرية ما قبل القديمة، أو المصرية العتيقة

- المصرية القديمة القياسية

- المصرية الوسيطة

- المصرية القديمة

- المصرية المتأخرة

- المصرية المتأخرة

- المصرية الديموطية

- القبطية

- المصرية المبكرة، المصرية الأقدم، أو المصرية الكلاسيكية

تنقسم اللغة المصرية القديمة تقليديأً إلى ستة أقسام رئيسية مرتبة زمنياً:[25]

- المصرية العتيقة (قبل 2600 ق.م.)، لغة معاد بناؤها من عصر الأسرات المبكرة.

- المصرية القديمة (ح. 2600–2000 ق.م.)، لغة الدولة القديمة.

- المصرية الوسيطة (ح. 2000–1350 ق.م.)، لغة الدولة الوسطى إلى أوائل الدولة الحديثة واستمرت كلغة أدبية حتى القرن الرابع.

- المصرية المتأخرة (ح. 1350-700 ق.م.)، من حقبة العمارنة إلى الفترة الانتقالية الثالثة.

- المصرية الديموطية (ح. 700 ق.م.-400 م)، وهي اللغة العامية في العصر المتأخر، ومصر الپطلمية ومصر الرومانية المبكرة.

- القبطية (بعد ح. 200 م)، وهي اللغة العامية في وقت التنصير، واللغة الشعائرية في للمسيحية المصرية.

كانت اللغة المصرية القديمة والسيطة والمتأخرة تُكتب باستخدام كل من الهيروغليفية والهيراطية. الخط الديموطية هو اسم الخط المشتق من الخط الهيراطي الذي بدأ في القرن السابع ق.م..

اشتُقت الأبجدية القبطية من الأبجدية اليونانية، مع بعض التعديلات على علم الأصوات المصري. وقد تم تطويرها لأول مرة في العصر الپطلمي، وحلت تدريجيًا محل الكتابة الديموطية في حوالي القرنين الرابع والخامس من العصر المسيحي.

المصرية القديمة

يُستخدم مصطلح "المصرية القديمة" أحيانًا للإشارة إلى أقدم استخدام للهيروغليفية، من أواخر الألفية الرابعة إلى أوائل الألفية الثالثة ق.م. في المرحلة الأولى، حوالي عام 3300 ق.م، لم تكن الهيروغليفية نظام كتابة متطور بالكامل، حيث كانت في مرحلة انتقالية من الكتابة الأولية؛ وعلى مدار الوقت الذي سبق القرن السابع والعشرين ق.م، يمكن ملاحظة ظهور سمات نحوية مثل تشكيل النسبة.[26][27]

يرجع تاريخ اللغة المصرية القديمة إلى أقدم جملة كاملة معروفة عُثر عليها، والتي تتضمن فعل مسند. وقد أُكتشِف ختمٌ في مقبرة ست - پر إب سن (يرجع تاريخه إلى حوالي 2690 ق.م.)، منقوش عليه:

![D46 [d] d](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_D46.png?1dee4)

![I10 [D] D](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_I10.png?9f0b0)

![N35 [n] n](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_N35.png?fcc27)

![I9 [f] f](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_I9.png?fe540)

![N35 [n] n](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_N35.png?fcc27)

![I9 [f] f](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_I9.png?fe540)

![X1 [t] t](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_X1.png?f2a8c)

![X1 [t] t](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_X1.png?f2a8c)

![S29 [s] s](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_S29.png?58979)

![N35 [n] n](/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_N35.png?fcc27)

d(m)ḏ.n.f tꜣ-wj n zꜣ.f nsw.t-bj.t(j) pr-jb.sn(j) يوحد .PRF.هو[28] land.two for son.his sedge-bee house-heart.their "لقد وحّد الأرضين لابنه، الملك المزدوج پر إب سن".[29]

تظهر نصوص موسعة من حوالي عام 2600 ق.م.[27] تُعَد نصوص الأهرام أكبر مجموعة من النصوص المكتوبة في هذه المرحلة من اللغة. ومن بين السمات المميزة لها استخدام ثلاثة أشكال من الرسومات الفكرية والصوتية والمعنوية للإشارة إلى صيغة الجمع. بشكل عام، لا تختلف هذه النصوص بشكل كبير عن اللغة المصرية الوسيطة، وهي المرحلة الكلاسيكية من اللغة، على الرغم من أنها تستند إلى لهجة مختلفة.

في عهد الأسرة الثالثة (ح. 2650 ق.م)، تم تنظيم العديد من مبادئ الكتابة الهيروغليفية. ومنذ ذلك الوقت، وحتى استبدال النص بنسخة مبكرة من القبطية (ح. القرنين الثالث والرابع)، ظل النظام دون تغيير تقريبًا. حتى أن عدد العلامات المستخدمة ظل ثابتًا عند حوالي 700 لأكثر من 2000 سنة.[30]

المصرية الوسيطة

كانت اللغة المصرية الوسيطة تُتحدث بها منذ حوالي 700 سنة، بدءًا من حوالي عام 2000 ق.م.، خلفي عهد الدولة الفرعونية الوسطى والفترة الانتقالية الثانية اللاحقة.[12] وباعتبارها النسخة الكلاسيكية للغة المصرية، فإن اللغة المصرية الوسيطة هي أفضل نسخة موثقة من اللغة، وقد جذبت أكبر قدر من الاهتمام بعيدًا عن علم المصريات. في حين أن معظم اللغة المصرية الوسيطة تُرى مكتوبة على الآثار بالهيروغليفية، فقد كُتبت أيضًا باستخدام النسخة المتصلة، والهيراطية ذات الصلة.[31]

أصبحت اللغة المصرية الوسيطة متاحة لأول مرة للعلماء المعاصرين مع فك رموز الهيروغليفية المصرية في أوائل القرن التاسع عشر. عام 1894 نشر أدولف إيرمان أول قواعد اللغة المصرية الوسيطة، وتجاوزه عمل ألان گاردينر عام 1927. ومن ذلك الحين، تم فهم اللغة المصرية الوسطى جيدًا، على الرغم من أن بعض نقاط تصريف الفعل المصري ظلت مفتوحة للمراجعة حتى منتصف القرن العشرين، ويرجع ذلك بشكل خاص إلى مساهمات هانز جاكوب پولوتسكي.[32][33]

يُعتقد أن المرحلة المصرية الوسيطة انتهت في حوالي القرن الرابع عشر ق.م، مما أدى إلى ظهور مرحلة اللغة المصرية المتأخرة. حدث هذا التحول في الفترة اللاحقة من الأسرة المصرية الثامنة عشرة (المعروفة باسم حقبة العمارنة).[بحاجة لمصدر]

المصرية التقليدية

ظلت النصوص المصرية القديمة والوسيطة الأصلية مستخدمة بعد القرن الرابع عشر ق.م. واستُخدمت محاكاة للغة المصرية الوسطى بشكل أساسي، لكن أيضًا بخصائص مصر القديمة والمصرية المتأخرة والديموطيقية، والتي أطلق عليها العلماء "المصرية التقليدية" أو "المصرية الوسيطة-الجديدة"، كلغة أدبية للنصوص الجديدة منذ أواخر الدولة الحديثة في النصوص الهيروغليفية والهيراطية الرسمية والدنية مفضلة على المصرية المتأخرة أو الديموطية. وظلت اللغة المصرية التقليدية كلغة دينية حتى دخول المسيحية مصر الرومانية في القرن الرابع.

المصرية المتأخرة

كانت اللغة المصرية المتأخرة تستخدم لمدة 650 عامًا تقريبًا، بدءًا من حوالي عام 1350 ق.م، أثناء الدولة المصرية الحديثة. نجحت اللغة المصرية المتأخرة لكنها لم تحل محل اللغة المصرية الوسيطة كلغة أدبية تمامًا، وكانت أيضًا لغة إدارة للدولة الحديثة.[6][34]

ترجع النصوص المكتوبة بالكامل باللغة المصرية المتأخرة إلى الأسرة العشرين وما بعدها. تمثل اللغة المصرية المتأخرة مجموعة كبيرة من الأدب الديني والعلماني، بما في ذلك أمثلة مثل قصة ون آمون، وقصائد الحب في بردية تشستر-بيتي الأول، وتعليمات آني. أصبحت تعليمات التعليمات نوعًا أدبيًا شائعًا في الدولةالحديثة، والتي اتخذت شكل نصيحة حول السلوك القويم. كانت اللغة المصرية المتأخرة أيضًا لغة إدارة للدولة الحديثة.[35][36]

اللغة المصرية المتأخرة ليست مختلفة تمامًا عن اللغة المصرية الوسيطة، حيث تظهر العديد من "الكلاسيكيات" في الوثائق التاريخية والأدبية لهذه المرحلة.[37] ومع ذلك، فإن الفارق بين اللغة المصرية الوسيطة والمتأخرة أكبر من الفارق بين اللغة المصرية الوسيطة والقديمة. كانت اللغة المصرية في الأصل لغة تركيبية، وبحلول مرحلة اللغة المصرية المتأخرة أصبحت لغة تحليلية.[38] وُصفت العلاقة بين اللغة المصرية الوسيطة واللغة المصرية المتأخرة بأنها مماثلة للعلاقة بين اللاتينية والإيطالية.[39]

- كانت اللغة المصرية المتأخرة المكتوبة تمثل بشكل أفضل من اللغة المصرية الوسيطة للغة المنطوقة في الدولة الحديثة وما بعدها: حيث تم إسقاط الحروف الساكنة الضعيفة ꜣ, w, j، بالإضافة إلى النهاية المؤنثة .t بشكل متزايد، على ما يبدو لأنها لم تعد تُنطق.

- أُستخدمت ضمائر الإشارة pꜣ (للمذكر)، وtꜣ (للمؤنث)، وnꜣ (للجمع) كأدوات.

- أُستبدل الشكل القديم sḏm.n.f (سمع) بالصيغة sḏm-f التي كانت لها جوانب مستقبلية (سيسمع) وكاملة (سمع). كما تم تشكيل زمن الماضي باستخدام الفعل المساعد jr (صنع)، كما في jr.f saḥa.f (اتهمه).

- الصفات للأسماء كانت تستبدل في كثير من الأحيان بالأسماء.

يُعتقد أن مرحلة اللغة المصرية المتأخرة قد انتهت في حوالي القرن الثامن ق.م، مما أدى إلى ظهور المرحلة الديموطية.

الديموطية

الديموطية هي تطور لاحق للغة المصرية المكتوبة بالخط الديموطي، بعد اللغة المصرية المتأخرة وسبقت اللغة القبطية، والتي تشترك معها في الكثير. في المراحل المبكرة من الديموطية، مثل تلك النصوص المكتوبة بالخط الديموطي المبكر، ربما كانت تمثل اللغة المنطوقة في ذلك الوقت. ومع ذلك، مع تزايد اقتصار استخدامها على الأغراض الأدبية والدينية، انحرفت اللغة المكتوبة أكثر فأكثر عن الشكل المنطوق، مما أدى إلى ازدواجية كبيرة بين النصوص الديموطية المتأخرة واللغة المنطوقة في ذلك الوقت، على غرار استخدام اللغة المصرية الوسيطة الكلاسيكية خلال العصر الپطلمي.

القبطية

القبطية هو الاسم الذي أُطلق على اللغة العامية المصرية المتأخرة عندما كانت مكتوبة بأبجدية يونانية، أي الأبجدية القبطية؛ وقد ازدهرت منذ زمن المسيحية المبكرة (و. 31/33-324)]]، لكن العبارات المصرية المكتوبة بالأبجدية اليونانية ظهرت لأول مرة خلال الفترة الهلينية ح. القرن الثالث ق.م،[40] حيث كان أول نص قبطي معروف، وثني أيضًا (القبطية القديمة)، من القرن الأول الميلادي.

ظلت اللغة القبطية موجودة حتى العصور الوسطى، لكن بحلول القرن السادس عشر بدأت في التضاؤل بسرعة بسبب اضطهاد المسيحيين الأقباط في ظل حكم المماليك. وربما ظلت اللغة القبطية موجودة في الريف المصري كلغة منطوقة لعدة قرون لاحقة. كما بقيت اللغة القبطية كلغة شعائرية للكنيسة الأرثوذكسية القبطية والكنيسة الكاثوليكية القبطية.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

اللهجات

إن أغلب النصوص المصرية الهيروغليفية مكتوبة بلغة السجلاات الفصحى وليست تنويعة عامية لمؤلفها. ونتيجة لهذا فإن الاختلافات اللهجية لا تظهر في اللغة المصرية المكتوبة حتى اعتماد الأبجدية القبطية. ومع ذلك فمن الواضح أن هذه الاختلافات كانت موجودة قبل العصر القبطي. في إحدى الرسائل المصرية المتأخرة (يرجع تاريخها إلى حوالي 1200 ق.م.)، يمزح أحد الكتبة بأن كتابات زميله غير متماسكة مثل "كلام رجل من الدلتا مع رجل من إلفنتين".[3][4]

في الآونة الأخيرة، عُثر على بعض الأدلة على وجود لهجات داخلية في أزواج من الكلمات المتشابهة في اللغة المصرية، والتي قد تكون مشتقة من اللهجات الشمالية والجنوبية المصرية، بناءً على أوجه التشابه مع اللهجات القبطية اللاحقة.[41] تحتوي اللغة القبطية المكتوبة على خمس لهجات رئيسية، تختلف بشكل رئيسي في التوافقات التصويرية، وأبرزها اللهجة الصعيدية الجنوبية، واللهجة الكلاسيكية الرئيسية، واللهجة البحيرية الشمالية، المستخدمة حاليًا في خدمات الكنيسة القبطية.[3][4]

نظم الكتابة

معظم النصوص الباقية من اللغة المصرية مكتوبة على الحجر بالهيروغليفية المصرية. الاسم الأصلي للكتابة الهيروغليفية المصرية هو zẖꜣ n mdw-nṯr ("كتابة كلمات الآلهة").[42][بحاجة لمصدر]

في العصور القديمة، كانت أغلب النصوص تُكتب على ورق البردي القابل للتلف بالخط الهيراطيقي والديموطي (لاحقًا). كان هناك أيضًا شكل من أشكال الهيروغليفية المنسوخة، التي استُخدمت في الوثائق الدينية على ورق البردي، مثل كتاب الموتى في عهد الأسرة العشرين؛ كانت أسهل في الكتابة من الهيروغليفية في النقوش الحجرية، لكنها لم تكن منسوخة مثل الهيراطية وافتقرت إلى الاستخدام الواسع النطاق للوصلات الأبجدية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، كان هناك مجموعة متنوعة من الهيروغليفية المنحوتة على الحجر، والمعروفة باسم "الهيراطيقية الحجرية".[بحاجة لمصدر]

في المرحلة النهائية من تطور اللغة، حلت الأبجدية القبطية محل نظام الكتابة القديم.

تُستخدم الحروف الهيروغليفية بطريقتين في النصوص المصرية: كرسم فكري لتمثيل الفكرة التي تصورها الصور، والأكثر شيوعًا، كرسم صوتي لتمثيل قيمتها الصوتية.

نظرًا لأنه لا يمكن معرفة التجسيد الصوتي للغة المصرية على وجه اليقين، يستخدم علماء المصريات نظام الترجمة الصوتية للإشارة إلى كل صوت يمكن تمثيله بواسطة الهيروغليفية أحادية الحرف.[43]

زعم الباحث المصري جمال مختار أن مخزون الرموز الهيروغليفية مشتق من "الحيوانات والنباتات المستخدمة في العلامات [والتي] هي أفريقية في الأساس" وفي "فيما يتعلق بالكتابة، رأينا أن الأصل النيلي البحت، وبالتالي الأفريقي، ليس مستبعدًا فحسب، بل ربما يعكس الواقع" على الرغم من أنه أقر بأن الموقع الجغرافي لمصر جعلها مستودعًا للعديد من التأثيرات.[44]

علم الصوتيات

في حين يمكن إعادة بناء علم الأصوات الصامتة للغة المصرية، فإن علم الأصوات الدقيق غير معروف، وهناك آراء متباينة حول كيفية تصنيف الأصوات الفردية. بالإضافة إلى ذلك، نظرًا لأن اللغة المصرية مسجلة على مدار 2000 سنة كاملة، فإن المرحلتين القديمة والمتأخرة منفصلتان بمقدار الوقت الذي يفصل بين اللاتينية القديمة والإيطالية الحديثة، فلا بد أن تكون قد حدثت تغييرات صوتية كبيرة خلال هذا الإطار الزمني الطويل.[45]

من الناحية الصوتية، قارن المصريون بين الحروف الصامتة الشفوية، والحنكية، واللهوية، والحنجرية. كما قارن المصريون بين الحروف الساكنة الصامتة والمؤكدة، كما هو الحال في اللغات الأفروآسيوية الأخرى، لكن الطريقة الدقيقة التي تم بها إدراك الحروف الساكنة المؤكدة غير معروفة. افترضت الأبحاث المبكرة أن التعارض في الوقفات كان تعارضًا في التعبير الصوتي، ولكن يُعتقد الآن أنه إما أحد الحروف tenuis وemphatic consonants، كما هو الحال في العديد من اللغات السامية، أو أحد aspired وejective consonants، كما هو الحال في العديد من اللغات الكوشية.[note 3]

نظرًا لأن الحروف المتحركة لم تُكتب إلا في اللغة القبطية، فإن إعادة بناء نظام الحروف المتحركة المصري أكثر غموضًا وتعتمد بشكل أساسي على الأدلة من اللغة القبطية وسجلات الكلمات المصرية، وخاصة الأسماء العلمية، في لغات/أنظمة كتابة أخرى.[46]

إن النطق الفعلي الذي تم إعادة صياغته بهذه الوسائل لا يستخدمه إلا عدد قليل من المتخصصين في اللغة. ولأغراض أخرى، يُستخدم النطق المصري، لكنه غالبًا ما لا يشبه ما هو معروف عن كيفية نطق اللغة المصرية.

- صامتة انفجارية

المصرية المبكرة

| صامتة شفهية | صامتة حنكية | صامتة غارية | صامتة طبقية | صامتة لهوية | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ترجمة صوتية | القيمة الصوتية التقريبية | ترجمة صوتية | القيمة الصوتية التقريبية | ترجمة صوتية | القيمة الصوتية التقريبية | ترجمة صوتية | القيمة الصوتية التقريبية | ترجمة صوتية | القيمة الصوتية التقريبية | |

| غير صوتية | p | [p] | t | [t] | ṯ | [c] | k | [k] | q (ḳ) | [q] |

| صوتية | b | [b] | ||||||||

| تفخيمية | d | [t'] | ḏ | [c'] | g | [k'] | ||||

في اللغة المصرية حرف g قد يعبر عن فونيمين (g1 وg²) [47]، كلاهما استمرار ل/g/ الأفرو-آسيوية.

Palatal /c/ ṯ (تفخيمية /c'/ ḏ) تستمر /q/ الأفرو-آسيوية و/k/ (وتُدمج مع t وd في الديموطية)

القبطية المبكرة

| صامتة شفهية | صامتة حنكية | صامتة غارية | صامتة طبقية | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| قواعد الكتابة | القيمة الصوتية التقريبية | قواعد الكتابة | القيمة الصوتية التقريبية | قواعد الكتابة | القيمة الصوتية التقريبية | قواعد الكتابة | القيمة الصوتية التقريبية | |

| غير صوتية | ⲡ | [p] | ⲧ | [t] | ϭ | [c] | ⲕ | [k] |

| صوتية | ⲇ | [d] | ⲅ | [g] | ||||

| تفخيمية | ⲇ | [t'] | ϫ | [c'] | ⲅ | [k'] | ||

- احتكاكية

| صامتة شفهية | صامتة حنكية | صامتة طبقية | صامتة حلقية | صامتة حنجرية | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

f |

|

s (ś) |

|

š |

|

ẖ |

|

ḥ |

|

h | ||||||||||||

|

z |

|

ḫ (x) |

|

ˁ |

|

(3, ȝ) | ||||||||||||||||

s وz تراجعت في الدولة الوسطى.

ˁ قد تكون /d/ في الدولة القديمة تطورت إلى حلقية في الدولة الوسطى. ويُطلق عليها "العين" المصرية مثل الحرف الاحتكاكي الحلقي السامي.

طبيعة ḫ مقابل ẖ هي محل جدل، قد تكون صوتية أو غير صوتية.

3، والتي غالبًا ما يتم التعرف عليها على أنها "ألف مصرية" (صوت لفظ الهمزة)، أو بدلاً من ذلك بقايا من صوت r أو l.

| |

ı͗، يحتمل أن تُنطق ألف ʔ].

| |

y (ı͗ı͗) [j]

| |

w, either of [w] and [u]

- Nasals

| |

m

| |

n

- Liquids

| |

r

l, in writing expressed as n, r, j, nr or 3[48] or often as the lion-shaped biliteral rw.

كما قد تُنطق الألف التقليدية (3) كحرف لثوي شبه ساكن /ɹ/.

نطق علم المصريات

كما هو متفق عليه، يستخدم علماء المصريات "النطق المصري" حيث تُعطى الحروف الصامتة قيمًا ثابتة وتُدرج الحروف الصائتة وفقًا لقواعد تعسفية في الأساس. غالبًا ما يتم نطق حرفين صامتين مختلفين ومميزين، الألف المصرية والعين المصرية، على النحو التالي [a]. يُنطق حرف الياء على النحو التالي [i]، وبالمثل، يُنطق حرف الـw على النحو التالي [u]. ثم يُدرج [e] بين الحروف الصامتة الأخرى. على سبيل المثال، يُنسخ الملك المصري الذي يُنطق اسمه بدقة على النحو التالي Rˁ-ms-sw على النحو التالي "Ramesses"، بمعنى "رع خلقه (حرفيًا، "ابن رع")".

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

التحول إلى القبطية

| حرف صامت مصري (وسيط) | حرف صامت قبطي (صعيدي) |

|---|---|

| 3 | y, i |

| ṯ | t |

| ḏ | t, d |

| k | k, g |

| ḫ, ẖ, š | š, ḫ, h, ẖ |

علم الصرف

اللغة المصرية قياسية إلى حد ما للغة الأفرو-آسيوية حيث أن جوهر مفرداتها غالبًا ما يكون جذرًا من ثلاثة أحرف صامتة، لكن في بعض الأحيان لا يوجد سوى حرفين صامتين في الجذر: rꜥ(w) ([riːʕa]، "الشمس" - يُعتقد أن [ʕ] كان حرفاً احتكاكياً بلعومياً صوتياً نوعاً ما). الجذور الأكبر شائعة أيضًا ويمكن أن تحتوي على ما يصل إلى خمسة أحرف صامتة: sḫdḫd ("يكون مقلوبًا").

تُضاف الحروف الصامتة والصائتة الأخرى إلى الجذر لاستخلاص معاني مختلفة، كما هو الحال في العربية والعبرية واللغات الأفروآسيوية الأخرى. ومع ذلك، نظرًا لأن الحروف الصائتة وأحيانًا الحروف الصامتة لا تُكتب بأي خط مصري باستثناء القبطية، فقد يكون من الصعب إعادة بناء الأشكال الفعلية للكلمات. وبالتالي، يمكن أن تمثل stp إملائياً ("الاختيار")، على سبيل المثال، يمكن أن يمثل الفعل الخبري (التي يمكن ترك نهاياته دون التعبير عنه)، أو الصيغ imperfective أو حتى اسم مصدر ("اختيار").

الأسماء

الأسماء المصرية كانت إما مذكر أو مؤنث (يشار إليها في اللغات الأفرو-آسيوية الأخرى بإضافة-t)، ومفرد وجمع (-w / -wt)، أو مثنى (-wy / -ty).

أدوات التعريف لم تتطور حتى المصرية المتأخرة، لكنها أصبحت تستخدم على نطاق واسع فيما بعد.

الضمائر

يوجد في اللغة المصرية ثلاث أنواع من الضمائر الشخصية: اللاحقة، enclitic (يطلق عليها علماء المصريات "مستقلة") وأسماء غير مستقلة. كما أنها تحتوي على عدد من النهايات الفعلية المضافة إلى صيغة المصدر لتشكيل الأفعال الخبرية، والتي يعتبرها بعض اللغويين[49] كمجموعة "رابعة" من الضمائر الشخصية. وهي تشبه إلى حد كبير نظيراتها في اللغة السامية والأمازيغية. المجموعات الثلاث الرئيسية من الضمائر الشخصية هي كما يلي:

| اللاحقة | مستقلة | غير مستقلة | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| الشخص الأول |

المفرد | .j or .ı͗ | wj or wı͗ | jnk or ı͗nk | |

| الجمع | .n | n | jnn or ı͗nn | ||

| الشخص الثاني |

المفرد | المذكر | .k | ṯw | ntk |

| المؤنث | .ṯ | ṯn | ntṯ | ||

| الجمع | .ṯn | ṯn | ntṯn | ||

| الشخص الثالث |

المفرد | المذكر | .f | sw | ntf |

| المؤنث | .s | sj | nts | ||

| الجمع | .sn | sn | ntsn | ||

ويوجد أيضاً أسماء إشارة (هذا، ذلك، هؤلاء، أولئك)، للمذكر، المؤنث وللجمع المشترك:

| المفرد | الجمع | المعنى | |

|---|---|---|---|

| المذكر | المؤنث | ||

| pn | tn | nn | "هذا، ذاك، هؤلاء، أولئك" |

| pf | tf | nf | "ذالك، أولئك" |

| pw | tw | nw | "هذا، ذلك، هؤلاء، أولئك" (القديمة) |

| pꜣ | tꜣ | nꜣ | "هذا، ذلك، هؤلاء، أولئك" (في المصرية المبكرة والمتأخرة) |

وأخيرًا، فإن أدوات الاستفهام تشبه إلى حد كبير نظيراتها في اللغات السامية والأمازيغية:

| الأداة | المعنى | الاستقلالية |

|---|---|---|

| mj or mı͗ | "من؟ ماذا؟" | مستقلة |

| ptr | "من؟ ماذا؟" | مستقلة |

| jḫ | "ماذا؟" | غير مستقلة |

| jšst or ı͗šst | "ماذا؟" | مستقلة |

| zy | "ماذا؟" | مستقلة، غير مستقلة |

الأفعال

قد تكون الأفعال المصرية مسندة أو غير مسندة.

تعبر الأفعال المسندة تعبر عن شخص، زمن/جانب، حالة وصوت. يشار إلى كل منها بمجموعة من البادئات الصرفية المرفقة بالفعل: على سبيل المثال، التصريف الأساسي للفعل sḏm ("يسمع") هو sḏm.f ("يسمع").

تأتي الأفعال غير المسندة بدون فاعل وهي أسماء المفعول وصيغة المصدر المنفية، والتي يطلق عليها كتاب قواعد اللغة المصرية: مقدمة لدراسة الهيروغليفية "المتممة المنفية". هناك نوعان رئيسيان من الأزمنة/الجوانب في اللغة المصرية: صيغة الماضي and temporally-unmarked imperfective and aorist forms. يتم تحديد الأخير من سياقه النحوي.

الصفات

Adjectives agree in gender and number with the nouns they modify:

Attributive adjectives in phrases are after the nouns they modify: nṯr ꜥꜣ ("[the] great god").

However, when they are used independently as a predicate in an adjectival phrase, as ꜥꜣ nṯr ("[the] god [is] great", حرفياً "great [is the] god"), adjectives precede the nouns they modify.

حروف الجر

Egyptian makes use of prepositions.

| m | "in, as, with, from" |

| n | "to, for" |

| r | "to, at" |

| jn or ı͗n | "by" |

| ḥnꜥ | "with" |

| mj or mı͗ | "like" |

| ḥr | "on, upon" |

| ḥꜣ | "behind, around" |

| ẖr | "under" |

| tp | "atop" |

| ḏr | "since" |

المفعول به

Adverbs, in Egyptian, are at the end of a sentence: For example:

Here are some common Egyptian adverbs:

| jm or ı͗m | "there" |

| ꜥꜣ | "here" |

| ṯnj or ṯnı͗ | "where" |

| zy-nw | "when" (حرفياً "which moment") |

| mj-jḫ or mı͗-ı͗ḫ | "how" (حرفياً "like-what") |

| r-mj or r-mı͗ | "why" (حرفياً "for what") |

| ḫnt | "before" |

النحو

Old Egyptian, Classical Egyptian, and Middle Egyptian have verb-subject-object as the basic word order. For example, the equivalent of "he opens the door" would be wn s ꜥꜣ ("opens he [the] door"). The so-called construct state combines two or more nouns to express the genitive, as in Semitic and Berber languages. However, that changed in the later stages of the language, including Late Egyptian, Demotic and Coptic.

The early stages of Egyptian have no articles, but the later forms use pꜣ, tꜣ and nꜣ.

As with other Afroasiatic languages, Egyptian uses two grammatical genders: masculine and feminine. It also uses three grammatical numbers: singular, dual and plural. However, later Egyptian has a tendency to lose the dual as a productive form.

الذكرى

The Egyptian language survived through the Middle Ages and into the early modern period in the form of the Coptic language. Coptic survived past the 16th century only as an isolated vernacular and as a liturgical language for the Coptic Orthodox and Coptic Catholic Churches. Coptic also had an enduring effect on Egyptian Arabic, which replaced Coptic as the main daily language in Egypt; the Coptic substratum in Egyptian Arabic appears in certain aspects of syntax and to a lesser degree in vocabulary and phonology.

In antiquity, Egyptian exerted some influence on Classical Greek, so that a number of Egyptian loanwords into Greek survive into modern usage. Examples include:

- ebony (Egyptian hbnj, via Greek and then Latin)

- ivory (Egyptian ꜣbw, via Latin)

- natron (Egyptian nṯrj, via Greek)

- lily (Egyptian ḥrrt, Coptic hlēri, via Greek)

- ibis (Egyptian hbj, via Greek)

- oasis (Egyptian wḥꜣt, via Greek)

- barge (Egyptian bꜣjr, via Greek))

- possibly cat[note 4]

- pharaoh (Egyptian pr ꜥꜣ, حرفياً "great house", via Hebrew and Greek)

The Hebrew Bible also contains some words, terms, and names that are thought by scholars to be Egyptian in origin. An example of this is Zaphnath-Paaneah, the Egyptian name given to Joseph.

The etymological root of "Egypt" is the same as Copts, ultimately from the Late Egyptian name of Memphis, Hikuptah, a continuation of Middle Egyptian ḥwt-kꜣ-ptḥ (حرفياً "temple of the ka (soul) of Ptah").[50]

انظر أيضاً

الهوامش

- ^ Whence the designation Kemic for Egypto-Coptic with km.t */kū́m˘t/ "black land, Egypt", as opposed to ṭšr.t "red land, desert". Proposed by Schenkel (1990:1)

- ^ أ ب The language may have survived in isolated pockets in Upper Egypt as late as the 19th century, according to Quibell, James Edward (1901). "When did Coptic become extinct?". Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde. 39: 87. In the village of Pi-Solsel (Az-Zayniyyah, El Zenya or Al Zeniya north of Luxor), passive speakers were recorded as late as the 1930s, and traces of traditional vernacular Coptic reported to exist in other places such as Abydos and Dendera, see Vycichl, Werner (1936). "Pi-Solsel, ein Dorf mit koptischer Überlieferung" [Pi-Solsel, a village with Coptic tradition] (PDF). Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo (MDAIK) (in الألمانية). 6: 169–175.

- ^ See Peust (1999), for a review of the history of thinking on the subject; his reconstructions of words are nonstandard.

- ^ Possibly the precursor of Coptic šau ("tomcat") suffixed with feminine -t, but some authorities dispute this, e.g. Huehnergard, John (2007). "Qiṭṭa: Arabic Cats". Classical Arabic Humanities in Their Own Terms. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004165731.i-612.89..

المصادر

- ^ أ ب Erman & Grapow 1926–1961.

- ^ "Ancient Sudan~ Nubia: Writing: The Basic Languages of Christian Nubia: Greek, Coptic, Old Nubian, and Arabic". ancientsudan.org. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 2017-03-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ أ ب ت ث Allen 2000, p. 2.

- ^ أ ب ت ث Loprieno 1995, p. 8.

- ^ Budge, E. A. Wallis (1920). Egyptian Hieroglyphic Dictionary (PDF). London: Harrison and sons. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-12-12.

- ^ أ ب Loprieno 1995, p. 7.

- ^ Grossman, Eitan; Richter, Tonio Sebastian (2015). "The Egyptian-Coptic language: its setting in space, time and culture". Egyptian-Coptic Linguistics in Typological Perspective. De Gruyter Mouton. p. 70. doi:10.1515/9783110346510.69. ISBN 9783110346510.

The Egyptian-Coptic language is attested in a vast corpus of written texts that almost uninterruptedly document its lifetime over more than 4,000 years, from the invention of the hieroglyphic writing system in the late 4th millennium BCE, up to the 14th century CE. Egyptian is thus likely to be the longest-attested human language known.

- ^ Layton, Benjamin (2007). [[[:قالب:Google books URL]] Coptic in 20 Lessons: Introduction to Sahidic Coptic with Exercises & Vocabularies]. Peeters Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 9789042918108.

The liturgy of the present day Coptic Orthodox Church in Egypt is written in a mixture of Arabic, Greek, and Bohairic Coptic, the ancient dialect of the Delta and the great monasteries of the Wadi Natrun. Coptic is no longer a living language.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ أ ب Loprieno 1995, p. 1.

- ^ أ ب ت Rubin 2013.

- ^ Frajzyngier, Zygmunt; Shay, Erin (2012-05-31). [[[:قالب:Google books URL]] The Afroasiatic Languages] (in الإنجليزية). Cambridge University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780521865333.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ أ ب Loprieno 1995, p. 5.

- ^ Allan, Keith (2013). [[[:قالب:Google books URL]] The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics]. OUP Oxford. p. 264. ISBN 978-0199585847. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Ehret, Christopher (1996). Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis, Ind.: Indianapolis Museum of Art. pp. 25–27. ISBN 0-936260-64-5.

- ^ Morkot, Robert (2005). The Egyptians: an introduction. New York: Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 0415271045.

- ^ Mc Call, Daniel F. (1998). "The Afroasiatic Language Phylum: African in Origin, or Asian?". Current Anthropology. 39 (1): 139–144. doi:10.1086/204702. ISSN 0011-3204. JSTOR 10.1086/204702.

- ^ Takács 2011, p. 13-14.

- ^ Takács 2011, p. 8.

- ^ Loprieno 1995, p. 31.

- ^ Takács 2011, p. 8-9.

- ^ Loprieno 1995, p. 52.

- ^ Loprieno 1995, p. 51.

- ^ Compiled and edited by Kathryn A. Bard with the editing assistance of Steven Blage Shubert. Bard, Kathryn A.; Steven Blake Shubert (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 274f. (in the section Egyptian language and writing). ISBN 978-0-415-18589-9.

- ^ Kupreyev, Maxim N. (2022) [copyright: 2023]. Deixis in Egyptian: The Close, the Distant, and the Known. Brill. p. 3.

- ^ "What Is the Egyptian Language?". GAT Tours (in الإنجليزية الأمريكية). 2019-12-11. Retrieved 2023-10-15.

- ^ Mattessich 2002.

- ^ أ ب Allen 2013, p. 2f..

- ^ Werning, Daniel A. (2008). "Aspect vs. Relative Tense, and the Typological Classification of the Ancient Egyptian sḏm.n⸗f". Lingua Aegyptia. 16: 289.

- ^ Allen (2013:2) citing Jochem Kahl, Markus Bretschneider, Frühägyptisches Wörterbuch, Part 1 (2002), p. 229.

- ^ "Hieroglyph | writing character". Encyclopædia Britannica (in الإنجليزية). Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ "Earliest Egyptian Glyphs – Archaeology Magazine Archive".

- ^ Polotsky, H. J. (1944). Études de syntaxe copte. Cairo: Société d'Archéologie Copte.

- ^ Polotsky, H. J. (1965). Egyptian Tenses. Vol. 2. Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities.

- ^ Meyers, op. cit., p. 209.

- ^ Loprieno, op.cit., p.7

- ^ Meyers, op.cit., p. 209

- ^ Haspelmath, op.cit., p.1743

- ^ Bard, op.cit., p.275

- ^ Christidēs et al. op.cit., p.811

- ^ Allen 2020, p. 3.

- ^ Satzinger 2008, p. 10.

- ^ Schiffman, Lawrence H. (2003-01-01). [[[:قالب:Google books URL]] Semitic Papyrology in Context: A Climate of Creativity: Papers from a New York University Conference Marking the Retirement of Baruch A. Levine] (in الإنجليزية). BRILL. ISBN 978-9004128859.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Allen 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Ancient Civilizations of Africa. Vol. 2 (Abridged ed.). London: J. Currey. 1990. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0852550928.

- ^ Lipiński, E. (Edward) (2001). Semitic languages : outline of a comparative grammar. Peeters. ISBN 90-429-0815-7. OCLC 783059625.

- ^ Eiland, Murray (2020). Interview with Bill Manley. "Champollion, Hieroglyphs, and Coptic Magical Papyri". Antiqvvs. 2 (1): 17.

- ^ Wolfgang Schenkel: Glottalisierte Verschlußlaute, glottaler Verschlußlaut und ein pharyngaler Reibelaut im Koptischen, Rückschlüsse aus den ägyptisch-koptischen Lehnwörtern und Ortsnamen im Ägyptisch-Arabischen. In: Lingua Aegyptia 10, 2002. S. 1-57 ISSN 0942-5659. S. 31 ff.

- ^ another interpretation is suggested by Christopher Ehret: Reconstructing Proto-Afroasiatic (Proto-Afrasian): Vowels, Tone, Consonants, and Vocabulary. University of California Publications in Linguistics 126, California, Berkeley 1996. ISBN 0520097998

- ^ Loprieno 1995, p. 65

- ^ Hoffmeier, James K (1 October 2007). "Rameses of the Exodus narratives is the 13th B.C. Royal Ramesside Residence". Trinity Journal: 1.

المراجع

- Allen, James P. (2000). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65312-1.

- Allen, James P. (2013). [[[:قالب:Google books URL]] The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study]. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-66467-8.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - Christidēs, Anastasios-Phoivos; Arapopoulou, Maria; Chritē, Maria (2007). A History of Ancient Greek: From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-83307-8.

- Haspelmath, Martin (2001). Language Typology and Language Universals: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-017154-6.

- Bard, Kathryn A. (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18589-0.

- Callender, John B. (1975). Middle Egyptian. Undena Publications. ISBN 978-0-89003-006-6.

- Loprieno, Antonio (1995). Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44384-5.

- Meyers, Eric M. (1997). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East.

- Satzinger, Helmut (2008). "What happened to the voiced consonants of Egyptian?" (PDF). Vol. 2. Acts of the X International Congress of Egyptologists. pp. 1537–1546. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-15.

- Schenkel, Wolfgang (1990). Einführung in die altägyptische Sprachwissenschaft. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Schenkel, Wolfgang (2012). Tübinger Einführung in die klassisch-ägyptische Sprache und Schrift, 7th rev. ed. Tübingen: Pagina.

- Vycichl, Werner (1983). Dictionnaire Étymologique de la Langue Copte. Leuven. ISBN 9782-7247-0096-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vycichl, Werner (1990). La Vocalisation de la Langue Égyptienne. Cairo: IFAO. ISBN 9782-7247-0096-1.

- Takács, Gábor (2011). "Semitic-Egyptian Relations". In Weninger, Stefan (ed.). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. de Gruyter Mouton.

- Allen, James P. (2020). [[[:قالب:Google books URL]] Ancient Egyptian Phonology]. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108751827. ISBN 978-1-108-48555-5. S2CID 216256704.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - Rubin, Aaron D. (2013). "Egyptian and Hebrew". In Khan, Geoffrey; Bolozky, Shmuel; Fassberg, Steven; Rendsburg, Gary A.; Rubin, Aaron D.; Schwarzwald, Ora R.; Zewi, Tamar (eds.). Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/2212-4241_ehll_EHLL_COM_00000721. ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3.

- Mattessich, Richard (2002). "The oldest writings, and inventory tags of Egypt". Accounting Historians Journal. 29 (1): 195–208. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.29.1.195. JSTOR 40698264. S2CID 160704269. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019.

مراجع أدبية

نظرة عامة

- Allen, James P., The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study, Cambridge University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1-107-03246-0 (hardback), ISBN 978-1-107-66467-8 (paperback).

- Loprieno, Antonio, Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-44384-9 (hardback), ISBN 0-521-44849-2 (paperback).

- Peust, Carsten (1999). Egyptian Phonology: An Introduction to the Phonology of a Dead Language. Peust & Gutschmidt. doi:10.11588/diglit.1167. ISBN 3-933043-02-6.

- Vergote, Jozef, "Problèmes de la «Nominalbildung» en égyptien", Chronique d'Égypte 51 (1976), pp. 261–285.

- Vycichl, Werner, La Vocalisation de la Langue Égyptienne, IFAO, Cairo, 1990. ISBN 9782-7247-0096-1.

علماء النحو

- Allen, James P., Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, first edition, Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-65312-6 (hardback) ISBN 0-521-77483-7 (paperback).

- Borghouts, Joris F., Egyptian: An Introduction to the Writing and Language of the Middle Kingdom, two vols., Peeters, 2010. ISBN 978-9-042-92294-5 (paperback).

- J. Cerny, S. Israelit-Groll, C. Eyre, A Late Egyptian Grammar, 4th, updated edition – Biblical Institute; Rome, 1984

- Collier, Mark, and Manley, Bill, How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs: A Step-by-Step Guide to Teach Yourself, British Museum Press (ISBN 0-7141-1910-5) and University of California Press (ISBN 0-520-21597-4), both 1998.

- Gardiner, Sir Alan H., Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, Griffith Institute, Oxford, 3rd ed. 1957. ISBN 0-900416-35-1.

- Hoch, James E., Middle Egyptian Grammar, Benben Publications, Mississauga, 1997. ISBN 0-920168-12-4.

- Selden, Daniel L., Hieroglyphic Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Literature of the Middle Kingdom, University of California Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-520-27546-1 (hardback).

قواميس

- Erman, Adolf; Grapow, Hermann (1926–1961). Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache [Dictionary of the Egyptian Language] (in الألمانية). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-05-002264-2.

- Faulkner, Raymond O., A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Griffith Institute, Oxford, 1962. ISBN 0-900416-32-7 (hardback).

- Lesko, Leonard H., A Dictionary of Late Egyptian, 2nd ed., 2 vols., B. C. Scribe Publications, Providence, 2002 et 2004. ISBN 0-930548-14-0 (vol.1), ISBN 0-930548-15-9 (vol. 2).

- Shennum, David, English-Egyptian Index of Faulkner's Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Undena Publications, 1977. ISBN 0-89003-054-5.

- Bonnamy, Yvonne and Sadek, Ashraf-Alexandre, Dictionnaire des hiéroglyphes: Hiéroglyphes-Français, Actes Sud, Arles, 2010. ISBN 978-2-7427-8922-1.

- Vycichl, Werner, Dictionnaire Étymologique de la Langue Copte, Peeters, Leuven, 1984. ISBN 2-8017-0197-1.

- fr (de Vartavan, Christian), Vocalised Dictionary of Ancient Egyptian (Open Access), Projectis Publishing, London, 2022. ISBN 978-1-913984-16-8. [Free PDF download: https://www.academia.edu/101048552/Vocalised_Dictionary_of_Ancient_Egyptian_Open_Access_]

قواميس أونلاين

- The Beinlich Wordlist, an online searchable dictionary of ancient Egyptian words (translations are in German).

- Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae, an online service available from October 2004 which is associated with various German Egyptological projects, including the monumental Altägyptisches Wörterbuch Archived 14 ديسمبر 2020 at the Wayback Machine of the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften (Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Berlin, Germany).

- Mark Vygus Dictionary 2018, a searchable dictionary of ancient Egyptian words, arranged by glyph.

Important Note: The old grammars and dictionaries of E. A. Wallis Budge have long been considered obsolete by Egyptologists, even though these books are still available for purchase.

More book information is available at Glyphs and Grammars.

وصلات خارجية

- Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae: Dictionary of the Egyptian language

- The Egyptian connection: Egyptian and the Semitic languages by Helmut Satzinger

- Ancient Egyptian in the wiki Glossing Ancient Languages (recommendations for the Interlinear Morphemic Glossing of Ancient Egyptian texts)